If you are looking for perfect holiday or birthday gift for the movie fan in your life, even yourself, I have the perfect recommendation. Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies is an extraordinary, 64-chapter anthology that contains five-decades of provocative, witty essays and insightful, one-of-a-kind interviews with the biggest directors, screenwriters and actors of all-time by, arguably, our foremost critic and historian. (He also cowrote the cult classic Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, received Emmy nominations for scripting AFI Life Achievement Award specials, and acted in Orson Welles’s legendary unfinished film The Other Side of the Wind.)

That profile doesn’t mention that he is a favorite of filmmakers (Guillermo del Toro recently voiced his admiration) and other film critics/historians, including myself. I have been reading Joseph McBride since we were classmates at the University of Wisconsin in the 1960s, when I was getting too many B minuses on my papers in film class and he was already publishing books. He was certainly one of my earliest inspirations. Joe and I began conversing passionately about movies 50 years ago, so it was with pleasure and ease last week that I had the following conversation with him about his 18th book.

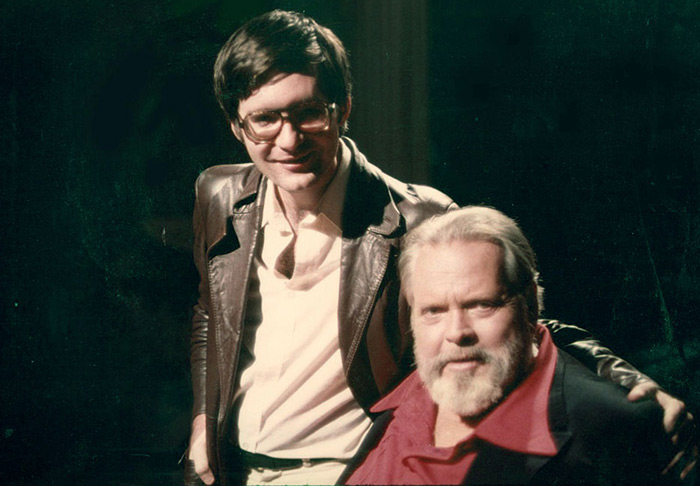

Joseph McBride with Orson Welles, 1978, Photo: Gary Graver

Danny Peary: Two Cheers for Hollywood follows your memoir from 2015, The Broken Places. As I read this collection of articles you wrote over five decades, all with a personal slant, I thought that it is in effect a second memoir. When assembling it, did you feel the same thing?

Joseph McBride: Yes, indeed. As I’ve grown older, I’ve shifted, as many writers do, into a retrospective/memoir vein to some extent. My 2013 book

Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit is also partly a memoir, as is my 2006 book

What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career. Going farther back to 1999,

The Book of Movie Lists is a memoir of my moviegoing experiences and tastes. But all of a writer’s books are personal. My biographies of Frank Capra, John Ford and

Steven Spielberg are as revealing of my personal views and feelings as anything else I’ve written.

In

Two Cheers for Hollywood, I had the pleasure of revisiting and reassessing my shorter writings on film over the past 50 years. It amazed me when I realized I’ve been at it that long! It truly seems like yesterday when I began. Each article, essay or interview has an introduction telling stories about how it was written, amusing and revealing incidents that took place around it, and retrospective views I have on the subject matter now. It was a lively and stimulating experience to put it all together. And I added five newly written pieces, including a career study of the blacklisted writer John Sanford and a monograph on the

Coen Bros.

DP: An anthology of your writings is long overdue. When did you start thinking about putting it together?

JM: Probably about 25 years ago. I experimented with different ways of doing it. I came up with some lists of articles to run in it and some means of arranging them. Acting on a friend’s suggestion, I tried centering the pieces on the auteur theory and how my views on that have evolved. It was interesting but seemed forced and to leave out too much. It also is hard to sell publishers on a personal anthology, so I decided to self-publish it, as I have done with Into the Nightmare and The Broken Places since that option recently became more viable. It gives me complete freedom to put together these highly personal projects the way I want. And the fulfillment house, Vervante, does a great job in printing on demand and shipping the books, which are ordered by readers via Amazon.

I recommend self-publishing to authors with quirky or difficult projects. But for my forthcoming book How Did Lubitsch Do It?, a critical study of the great German American director Ernst Lubitsch coming out next June, I went with Columbia University Press. One of my main motivations in writing that book is to make Lubitsch a household name again, and going with a regular publisher ensures more review attention and sales in bookstores. Much of the mainstream media still won’t review self-published books, though they will have to evolve on that. In the meantime authors rely on alternative media sites online and elsewhere and on enlightened publications such as yours.

DP: It is a massive volume, almost 700 pages, but did it take so long for you to tackle it because you knew you would have to leave out hundreds of quality articles?

JM: It actually took about a year to put Two Cheers together and supervise it through publication (with Maggie Hurley again as my ace designer). The longer part of the job was how I mulled over the structure and contents. I had spent a fair amount of time assembling a box of Xeroxes of all my magazine articles when I donated more of my papers to the Wisconsin Historical Society and sent them the original issues in 2008, so I had had a chance to sort through and re-read those, and I had them for easy reference when I was assembling Two Cheers. I had my choices digitized for editing and took it from there; it was a pleasurable task to revisit my past and reconsider it in the present.

DP: In the introduction, you write about having four parallel careers: “academic film scholarship and teaching; popular journalism in both mass market and trade publications; critical analysis and biography; and practical experience in the industry as a screenwriter and producer.” For many years I thought you were primarily a film critic/historian, but over time I’ve come to see you being foremost a journalist, even an investigator at times, as with your Into the Nightmare. I haven’t seen you teach in a classroom, but I have seen you lecture, and even there I detected a journalistic, reporter’s pursuit of truth. So I’d think that if you weren’t a skilled journalist, you couldn’t have been successful pursuing your other three careers.

JM: You’re right, and when I was interviewed in 2013 for a short online film profile as a faculty member at San Francisco State University, the filmmaker, Silvia Turchin, asked me for a self-description. I said, “If I had to define myself, I’d call myself an investigative reporter.” I surprised myself by saying that, but that’s how I’ve always conducted my career. As I’ve written in my memoirs, I had a repressive childhood being brainwashed as a Catholic schoolchild and was brainwashed by schools and the media about history and other subjects as well, so my passion has always been to find out things, to know how the world actually works. A 2011 documentary film about my career by Hart Perez is called Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. I supplied the title, because I’ve always gone behind the curtain since I became a professional journalist in 1960, and my film journalism, as in Two Cheers, goes behind the curtain of that often obfuscated and mythologized industry.

DP: You quote Samuel Fuller at various times in your book, and I wonder if you felt connected to him because he was a newspaperman like your Dad, Raymond McBride, and you always have been a reporter at heart? There’s a rawness to his ripped-from-the-headlines-of-scandal-sheets movies that I sense you could relate to when you were at a typewriter and trying to beat a deadline.

JM: Sam and I hit it off immediately. Old newspaper guys recognize each other and feel an affinity. I felt the same way when I met Penn Jones Jr., the crusading editor of the small-town Midlothian (Texas) Mirror, one of the first and most tenacious researchers of the assassination of President Kennedy. Sam and Penn were both feisty, no-nonsense guys who always were after scoops and were relentless truth-tellers. That’s how I’ve tried to be as well, and they were inspirational. I spent a lot of time with Sam over the years. He helped me with my screenwriting, and we started doing an interview book on his life, The Typewriter, the Rifle, and the Movie Camera, but I was awfully busy making a living, and I couldn’t keep him on track. I think we were up to around 1930 when we stopped. He spent three hours one night talking about meeting and despising Charles Lindbergh. Great stuff, and I have 18 hours of Fuller on tape, but . . .

Penn Jones was a mentor of mine in Dallas in helping me understand the assassination, which I began researching seriously in 1982. As I write in the introduction to Two Cheers, the assassination has been my main interest in life since I heard the news a few minutes after it happened. Actually I was interested in it before it happened. In October 1961 I wrote a short story for my freshman English class at Marquette University High School about the subject, called “The Plot Against a Country.” It may be the first literary treatment of the assassination, but it’s laughably bad, although prescient. I wrote it because I had become concerned about Kennedy’s vulnerability while working as a volunteer on his 1960 presidential primary campaign in Wisconsin, and I was already a student of the Lincoln assassination, so I knew such events usually are the result of plots.

DP: Why is your book title not Three Cheers for Hollywood?

JM: I borrowed the idea for my title from E. M. Forster, who wrote a book of essays called Two Cheers for Democracy. To paraphrase what he wrote, “We may still contrive to raise three cheers for Hollywood, although at present she only deserves two.” Actually, I thought I was being generous.

DP: You write in your intro: “We have to face the fact that we no longer live in an age of cinephilia. I would not be honest if I did not admit that makes me terribly sad.” I find that at a time when so many old films are available but new generations of film fans—and filmmakers—don’t bother to seek them out, my frustration runs neck and neck with my sadness.

JM: Peter Bogdanovich, who inspired me as a young writer and interviewer on film, has said it’s only films that are called “old”—people don’t speak of “old symphonies” or “old novels.” It is dismaying to find that many young people don’t even consider watching films that were made as recently as three or four years ago. It used to be five, and now the window keeps shrinking. I was surprised when I started teaching film full time in 2002 and realized students hadn’t seen

Annie Hall, which I naively thought everybody had seen, but I’m not surprised by that kind of response anymore. This goes along with a general ignorance of history.

It’s even more shocking how little young people know about world and American history; a survey a few years ago showed that a majority of American high school students think we were fighting the Russians in World War II and that Germany was our ally. Few know anything about what we used to be taught as “Civics.” Many don’t know what the three branches of our government are. That level of ignorance is dangerous. I believe this comes from a general collapse of our public education system that began with the so-called “tax revolt” of the 1970s. That was an excuse for a deliberate dumbing-down of the populace. Right-wingers want to keep the populace ignorant so they can to lie to them and put an ignoramus such as

Trump in power as a figurehead for their schemes.

I am afraid this is irreversible, though I try to teach history and literature through film to my students at San Francisco State (one called out during a Film and Society class, “I didn’t know this was a history class!”). I tell prospective filmmakers that your general education courses are the most important, because if all you know about are cameras and sound equipment, what are you going to make films about? This is a major reason why most films today are so bad. My introduction to Two Cheers is deeply pessimistic, although we can’t envision the future of what used to be called “film.” We just know that film as we knew it is over, though film history remains to be studied, even if much of it is lost.

DP: In the Introduction, you write that while you still love it, you no longer consider John Ford’s The Searchers your favorite film. It is still in my top five, somedays even number one, just like it was when you and I were becoming film fanatics in the fifties and sixties. I have found, surprisingly, that while some films have dated and I don’t have patience with some of my childhood favorites, my taste for significant films hasn’t really changed since we were in college, which is surprising because I now have a decades-older person’s perspective. What about you?

JM: I find that films seem to change as I do, though it’s mostly my perspective that has changed, and my life experience that makes them seem different or puts them in a new light. Some films I didn’t find interesting then, I find compelling now. But we do tend to revel in the films we loved as young people—in our case, in that Golden Age of cinephilia in the 1960s. I think I wore out The Searchers by seeing it too often, as I did to some extent with The Quiet Man and Citizen Kane. Also, The Searchers is literally not the same film we came to love in our youth. The yellow layer of the three-strip Technicolor has collapsed.

As you get older, films themselves do sometimes change. But over the years I began to be troubled by the inconsistencies and conflicts and incoherencies in The Searchers, great as it is in most ways. Those problems help make it so fascinating and are reflections of its honesty but also of Ford’s limitations. He was going beyond what he had done before but couldn’t go all the way with its implications (the same problem affects his later Cheyenne Autumn, as I discuss in my audio commentary on that film). The treatment of Marty’s Indian wife “Look” in The Searchers, for example, is deeply troubling. One of the best pieces of film criticism I have read is Peter Lehman’s essay on what he calls the missing shot in the Look sequence, the one that should have shown her crashing down as Marty kicks her off the hill; including that would have made it quite a different film.

DP: If you loved or disliked an old-time director back in the sixties, are you likely to feel the same about them?

JM: Usually. I love Ford and Orson Welles and Jean Renoir as much as ever. I am less interested in Luis Buñuel now, though, since I’ve largely worked through my old hangups about Catholicism. He is still great, of course, and he inspired me in my anticlerical rebellion period, but I no longer feel the need to revisit his work as often. I’ve grown more interested in some directors I didn’t know as well back then because of the vagaries of distribution or because of my youth. Yasujiro Ozu is now one of my favorites, as is Ernst Lubitsch, partly because I’ve now managed to see all their films. It was hard to see their work in the sixties. Ozu, with his concentration on the deterioration of family and society and on old age, means more to me than he would have when I was young.

DP: When asking that question, I remembered that John Huston had a rebirth and made great films in the 1970s, like Fat City, Wise Blood, and especially The Man Who Would Be King, long after his heyday and a few years after Andrew Sarris placed him in his “Less Than Meets the Eye” category in The American Cinema, so everyone’s impression of him might have changed for the better.

JM: He’s one of those good directors whose output nevertheless is very uneven. Welles almost never compromised as a director but often did so as an actor. Huston would compromise as a director by doing crummy projects to keep commercially viable so he could make his occasional masterpieces or highly personal projects. When he is most engaged, he is a splendid filmmaker, and he has an unusually wide range. I write in

Two Cheers about how Huston is the best filmmaker at adapting works of literature into cinematic form, and how he adapted such an amazing diversity of great writers, some of whose work was thought impossible to film, such as James Joyce,

Herman Melville and Flannery O’Connor.

DP: You were an early bloomer. Do you think you already had almost reached your pinnacle as a film critic and historian when you were in college? Or do you think you weren’t yet ready to do most of the critical and biographical writing and teaching you’d do years later?

JM: As I found while putting together Two Cheers, most of my early work for film magazines from 1967 onward is fairly polished and professional, since I did begin unusually young, partly because my parents were journalists and helped me along the path. My mother, Marian McBride, helped me get my first article sold to Young Catholic Messenger in 1960 for $40. It was on the great Milwaukee Braves pitcher Warren Spahn and his son Greg, a Little League teammate of mine. After that I was confident I could keep selling articles, a feeling that sustained me even though other articles I wrote on baseball failed to sell for years after that. I started writing my book High and Inside: An A-to-Z Guide to the Language of Baseball in 1963, but it was not published until 1980. I began writing my critical study Orson Welles in 1966; it was published by the British Film Institute in its Cinema One series in 1972.

Only when I started writing about film did I became successful at the craft of writing. My work has deepened over the years due to my greater life experience and knowledge base as an autodidact; that’s one reason my books have gotten longer! I also learned a lot from being a film reviewer and reporter for Daily Variety and Variety off and on from 1974 through 1992. Before going to work for Daily Variety in Hollywood, I had a hazy idea of how films were actually made. My 18 years as a screenwriter, though they were the worst years of my life other than my childhood, also helped me understand the business more deeply. I couldn’t have written my three major biographies without that knowledge of how things actually work in Hollywood. And through my film journalism and screenwriting I was able to make many contacts that paid off when I was writing biographies.

DP: In the sixties we were among the many who were staunch believers in auteurism and championed strong directors at the expense of screenwriters and producers. Among the few screenwriters we really cared about were those who were blacklisted, as well as a few screenwriters who collaborated frequently with our favorite directors. In your book, you say how much you enjoyed years later interviewing and writing articles about writers, and you have several chapters about them in your book. Did you have an awakening at some time when you discovered that writers were the unsung heroes of Hollywood?

JM: It took me a while, though I began writing screenplays in 1966, teaching myself by doing it. I was influenced at the start by Citizen Kane, whose great screenplay by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles was my model. I found a copy at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin (as it was then called) and spent a month typing an exact copy since I couldn’t afford to Xerox it. That helped me internalize the script, and I had a 16mm print of the film I ran endlessly. I kept writing scripts and made six short films in Madison, but my goal was to use screenwriting as an end to become a director. I have turned down some opportunities to direct films, so I guess I knew I wasn’t really suited for that profession. I became more conscious of how important screenwriters are when I worked with directors who took credit for my ideas or ripped off my work. And I became friendly with some veteran screenwriters, including blacklisted screenwriters I admired, such as Abraham Polonsky and John Sanford.

Their example, and studying the history of Hollywood more carefully, made me realize that Irving Thalberg was right when he (allegedly) said, “Screenwriters are the most important people in the business, but we must never let them find that out.” Some of the essays I have most enjoyed writing that appear in Two Cheers are career profiles of screenwriters I wrote for the Writers Guild of America magazine Written By. My biography Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success points out that Robert Riskin (especially) and other screenwriters were as much the authors of Capra’s work as Capra was. There’s a lot about screenwriters in my biographies of directors, which critically examine the auteur theory.

DP: Of course, before he became a director, Jean-Luc Godard was among first proponents of the auteur theory, along with François Truffaut at Cahiers du Cinema. I laughed when you recalled Godard’s visit to the University of Wisconsin in 1970 to show See You at Mao, because that was the first celebrity I ever sat around with and it probably was your first time—unless you’d already interviewed John Ford for your book on him—and it wasn’t the best experience! Maybe you tried to interview him when you were alone with him, because I didn’t remember that you were one of the five or six film people who sat at a table in the Rathskeller at the Memorial Union with our idol, and I’m sure you don’t remember I was there either because we were all a bit freaked out. Maybe we sat with him at different times with the same result! You remember a little verbal exchange with him. I remember almost nothing being said to him by us “brilliant” movie experts, because we were all so intimidated. A few years ago I mentioned this gathering to Anna Karina and she laughed because it was so like him—she was sure that though Godard came across as aloof and, as you recall, “surly,” and “obnoxious and intractable,” he too was too shy to talk about his movies. I know John Ford wasn’t the easiest of interviews, but did you ever have a similar encounter in Hollywood?

JM: The first movie celebrity I met was not Ford or Godard but Joe E. Brown. It was shortly after his memorable turn in the 1959 Billy Wilder film Some Like It Hot, and he came to our neighborhood in Wauwatosa to visit some friends. We kids went to the house and waited for him. He got out of a car and walked past us, scowling. I should have realized right then and there that I should not go into the movie business. (My brother Pat recalls Brown turning around at the doorway and giving us his trademark grin and a wave, but I don’t remember that.) But, yes, Godard was the rudest director I ever met. I think it’s overly generous to call him shy. He barely would talk to me when I did my article on his Madison visit that ran in Sight and Sound. When I wrote a reflection on that experience and his work for Two Cheers, I watched See You at Mao again and realized that it is the worst film I have ever seen except for Pearl Harbor; those two abysmal stinkers are closely followed by Eraserhead. Godard made John Ford seem like a pussycat.

I don’t remember you and those others being at the table in the Rathskeller; I am sure I would. When I tried to interview Godard, the other people at the table were Jean-Pierre Gorin, my friend Ellen Whitman, a

Grove Press publicist, and a photographer. Did I have similarly difficult encounters in Hollywood? Usually not, because people tend to be convivial when they want publicity. A few people wouldn’t talk. And there were some awkward encounters, but none jumps out as much as my attempt to interview astronaut Buzz Aldrin while I was a reporter with the Riverside

Press-Enterprise before joining

Daily Variety. I had an interview scheduled with Aldrin at a mall where he was signing a new book. I arrived, but he wouldn’t talk to me for some reason, which made the publicist upset. Aldrin has always been a crank. That was why NASA chose Neil Armstrong to walk on the Moon before him. I encountered some uncooperative people while doing my biographies, but most of the hundreds of people I approached for interviews on those books were helpful. I estimate I have interviewed about 15,000 people in my career as a journalist and historian.

DP: You quote writer-director Paul Schrader saying “People talk about the ‘Golden Age’ of Hollywood in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It wasn’t that the films were better or the filmmakers were better, it was the audiences that were better. It was a time of social stress, and audiences turned to artists for answers.” Do you agree with Schrader—and me—that the audiences in the sixties and early seventies were the best ever in the sense that they cared about themes as well as stars, and were into discovering art? I don’t necessarily believe that the films of the sixties were the best—though they revolutionized the medium—but I think all of us were so lucky because not only were there exciting new American and foreign directors, but also most of the great American and foreign directors of past decades were still making films. We could see new films by Welles, Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Fellini, Kurosawa, Siegel, Fuller, Antonioni, Bergman, Wilder, Capra, on and on—and old films to discover—Keaton, the Marx Brothers, It’s a Wonderful Life, The Searchers—were resurfacing. All genres, all countries. That’s how I felt when we were in Madison during that time. And I still think it was the greatest decade for becoming a movie fan.

JM: I still think the greatest era in Hollywood was the late silent period, when the art form reached its zenith. Mary Pickford said it would have been more logical for silent films to grow out of sound films rather than the other way around. Sunrise in 1927 was the pinnacle of the silent era. For a year when I was writing my Capra book and living in the San Bernardino Mountains, I would drive to lunch every day at Lake Arrowhead, where F. W. Murnau shot much of that masterpiece. The 1930s and forties were when many of my favorite films were made, and I saw a lot of great work while growing up in the fifties. I remember watching a lot of garbage in the sixties and seventies, partly because I had to review so many films, and at Daily Variety during that time I was mostly relegated to B movies, many of which were dogs, tawdry horror or revenge pix and the like.

So it’s like Melvyn Douglas once said about the 1930s, that he was flabbergasted when he heard young film buffs call it a golden age, although he and other actors remembered those years as a constant struggle to escape mediocre projects. I felt much that same sense of surprise when I began hearing people talking about the early-to-mid 1970s as Hollywood’s last golden age. Still, in one eight-month period in 1974, we had The Conversation, Chinatown, and The Godfather Part II, and we almost took it for granted that masterpieces would come along regularly. I didn’t think much of the audiences then, however, because too many good films were neglected (I am thinking especially of Polonsky’s 1969 radical Western Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, which I discuss with Abe and an uncomprehending audience in Two Cheers), and pretentious junk such as Easy Rider and The Graduate was celebrated. Too many of our would-be radical colleagues from that era became stockbrokers, and one even became a studio executive.

On the other hand, Errol Morris came out of our “Madison film mafia,” and he’s one of the great modern directors. He was a member of the Wisconsin Film Society, which I ran, but he was more interested in history, philosophy and Ed Gein (we bonded over our mutual obsession with that Wisconsin grave robber, the model for Norman Bates in Psycho). So I hold up Errol to students as an example of how just studying film is not the way to become a great filmmaker. But it’s true that a climate of cinephilia flourished in that turbulent social period of our youth. A time of unrest tends to lead to some great art. I remember 1968 being the worst year in American history since the Civil War. But the studios were collapsing then, and along with some horrendous dreck, we had some fresh and innovative films until the blockbuster syndrome and the Reagan era pretty much put an end to that.

DP: When you were at Wisconsin, did you already plan to head for Hollywood?

JM: My editor at The Wisconsin State Journal used to say I was the only reporter he knew who would walk around with a copy of Variety under his arm. I had Hollywood in mind from the time I first saw Citizen Kane in one of our three University of Wisconsin film classes in 1966 and was determined to make films and write about them. It took me until 1973 to make the move west, though, and I had to suffer through a year in godforsaken Riverside before I found the job on Daily Variety. I was driving back and forth from Riverside to Los Angeles many nights for film events and getting back home at two or three in the morning while stumbling in to work in a daze at 8 a.m.

DP: You write, “During my first week in Hollywood, in August 1970, I interviewed John Ford and Jean Renoir and met Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich. By the end of the week I was acting in the first day of shooting of Welles’s film The Other Side of the Wind.” Were you thinking that your first week in Hollywood could have been a movie?

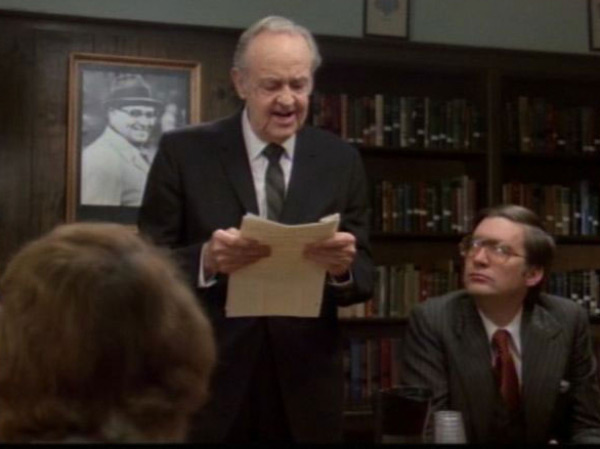

John Ford, Photo: Joseph McBride

JM: That never occurred to me. But I have often told that amazing story. I am in the upcoming documentary on The Other Side of the Wind, tentatively titled They’ll Love Me When I Am Dead, which is planned to premiere at Cannes in May with Other Wind itself, knock wood. I spent six years acting for Welles in that legendary feature, from the first day of shooting to the last. It and Variety were my film school.

I went to Hollywood that week in 1970 to interview Ford for the critical study Michael Wilmington was writing about him, which was not published until 1974. In Two Cheers I run virtually the entire unedited transcript of that wacky interview for the first time, and I realized that despite his intransigence, Ford gave me some good material. He actually announced his retirement in the course of the interview on August 19; much later I confirmed through studying his papers that it actually was the last day of his career, when he finally gave up after failing to get an Italian spaghetti Western financed with the help of his good friend Woody Strode. No wonder Ford was in a bad mood when I came to ask him about his classic movies. Later that Wednesday I interviewed Renoir, so I met my three favorite directors in one week. Alfred Hitchcock also agreed to be interviewed, but the hotel didn’t give me his message until too late. On the Friday, I met Welles for lunch and a three-hour chat, and on Sunday I was acting in his film and helping write my own dialogue. By Monday morning, August 24, I was back home in Madison and discovered that during the night radicals had blown up the Army Mathematics Research Center, an event I later worked into the ending of my script for Rock ’n’ Roll High School.

DP: I would ask you with tongue in cheek about what happened the second week, but you write, “I naively thought every week in Hollywood would be like this. Little did I know that week was the pinnacle.” That whirlwind of a first week was like winning a lottery ticket, but just from your book it’s apparent that you had many more high points in Hollywood, mingling with our movie idols, that I for one envy. When you wrote for Variety from 1974 to 1977 and 1980–81, you write that you were “able to visit studio sets and locations and watch many films being shot,” and “had the access to interview almost everyone who interested me in the business.” When you went home afterward, did you pinch yourself and say, “I just hung out with Orson Welles or John Wayne,” or were you always nonchalant about rubbing shoulders with our movie heroes?

JM: When I went back to Daily Variety in 1989–92, I realized the business had drastically changed. The corporations had taken over, and they made it difficult to get filmmakers on the phone or go on sets. So I had been covering Hollywood during the last times when that was regularly possible. I made a point of seeking out and interviewing everyone I could whose work I admired. I was never too jaded to be unexcited about meeting them, talking with them, and watching them at work. But that was a time when the true legends—even silent-movie people—were still around.

DP: Talk about how movies changed during the time you worked at Variety. Was it a subtle change or very obvious?

JM: I could see a sharp decline from the freer and more open atmosphere of the mid-1970s until the

Star Wars era began in 1977. When I saw the first Hollywood screening of that film, I was so depressed, I thought, “It’s over.” I could tell that cardboard juvenilia would be taking over, and as the Reagan era approached, the kinds of stories I wanted to tell were not welcome, such as a fun idea I had for a biopic of Fidel Castro; a

Battle of Algiers-influenced film about the Bay of Pigs invasion; and a black comedy about nuclear war that tried to out-

Strangelove Kubrick. Imagine the horror with which those pitches were greeted in Hollywood offices. The best script I ever wrote, the autobiographical story

The Broken Places,which was my

400 Blows, received a lot of praise but no takers, because it had a grim ending and Hollywood, unlike Europe, is not interested in personal stories. (I eventually turned it into a memoir, the form it should always have had.)

But I stubbornly persisted, with increasing frustration except for the five AFI Life Achievement Award specials I worked on, until I retired from screenwriting in 1984. I waited until I won the WGA award and received another WGA nomination and an Emmy nomination and was vested for a (modest) pension, so I was more or less going out on top. That and leaving the Catholic Church were the two hardest and most important decisions I ever made in my life, and both were literally life-saving.

DP: When you were working on the script for Allan Arkush’s anarchic Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, were you thinking about how the political climate was changing in the country and in Hollywood?

JM: Yes, and I knew we were squeaking in under the wire before Reagan got into office. I deliberately turned what started out as a frivolous teenage comedy into an anarchic political satire. Was it you who wrote, Danny, that it’s the only mainstream American film in which an important cultural institution is destroyed and no one is punished? I originally called the school Ronald Reagan High School and had a statue of him blown up, but Roger Corman vetoed that because he was a neighbor of Reagan’s in the Pacific Palisades. So I changed it to Vince Lombardi High School, after the Green Bay Packers’ football coach (I had sold hot dogs at Packers games in Milwaukee to help put myself through high school), and we blew up the school at the end. When Corman did the awful sequel, Rock ’n’ Roll High School Forever, in 1991, they called the school Ronald Reagan High School, because he had left office and it was safe to mock him. As Kurt Vonnegut would say, “So it goes.”

DP: You end your Intro with these five words: “Yes, I love movies, but . . .” I’d like you to expand on that . . .

JM: I feel I was betrayed by the movies, as I was by the Catholic Church, my parents, my schooling, and our government. It’s hard not to continue loving the movies I once loved, though, as well as some occasional new ones. My feelings about the medium today are highly ambivalent. I feel in a sense I went into the wrong profession. But my interests have always been broad, and I’ve incorporated them into my work. My biographies of directors range widely into sociopolitical subjects, and I recently have been branching out into books on other subjects besides movies. So I can’t regret the choices I made as a youth (once you make them, it’s almost impossible to turn back), but what happened to the art form I loved—it’s been trashed and turned largely into moronic fodder for the adolescent male audience—makes me beyond sad.

DP: It’s brave of you to begin a 700-page book with the “article I’m most proud of” instead of making it your final chapter. Why is it that you are that proud of your tribute to blacklisted screenwriter, Michael Wilson?

JM: It was only some time after writing my Capra biography that I realized that Michael Wilson is the true hero of that book, the man Capra should have been but failed to be. Capra informed on Wilson after he worked on It’s a Wonderful Life and the film version Capra didn’t make of Jessamyn West’s book The Friendly Persuasion (William Wyler later made the film version, Friendly Persuasion, and did not credit the blacklisted Wilson). Because Wilson was so valiant in standing up and speaking out for the First Amendment, I was honored to pay tribute to him in Written By. I am proud of that essay because I convey his greatness as a man and as a writer with revealing research, including an interview with his widow, Zelma, an architect who was blacklisted from her profession.

McBride with Frank Capra, 1985, Photo: Columbia Pictures

DP: This may be a silly question, but do you think that most screenwriters who worked with famous directors expected much attention and fan recognition for their contributions?

JM: No, they knew they were the lowest of the low in Hollywood, unfortunately. But the money was good if you were under contract in the old days. Occasionally a good film resulted, even if you were rewritten by others. But it was and is a miserable profession. Too many writers became cynical as a result. I admire the writers who took it seriously and tried to do good work nonetheless.

DP: I think most of the screenwriters you spoke to leaned to the left politically, but were you uncomfortable with directors and actors who leaned far to the right? Did you ever argue politics with them or did you settle into a neutral reporter mode?

JM: I might have done more, but when you interview someone you’re there more to listen than to argue, which can be counterproductive. To give one example, when I did

Into the Nightmare, I interviewed a retired Dallas police detective named Morris Brumley, who had been a boyhood friend of J. D. Tippit. As we talked in a diner with my tape recorder in front of us, Brumley began telling me how he had been a member of the

Ku Klux Klan and even showed me his Knights of the Ku Klux Klan membership card. He claimed he had “infiltrated” the KKK for the police, but he boasted about committing violence. I finally had to say something, so I asked if he had tried to arrest his fellow Klansmen, and that more or less stopped him from telling me much more, unfortunately. I wish I had challenged Howard Hawks more about his politics during the seven years I was doing our interview book

Hawks on Hawks. But I tried, and not much resulted. My biographies have a great deal about politics in them, especially the Capra book. I became more political as I went along.

DP: Were directors taken aback if you asked them about themes or ideas or had they experienced such interviews throughout their careers? Were most appreciative of the new interest in cinema in the sixties and seventies and the curiosity about the films they’d made years before?

JM: I found I had an affinity with older directors partly because they were also marginalized. They were outsiders like I was as an aspiring screenwriter who was also a film historian, looking from the outside in as much as from the inside out. I felt closer to older directors than I did to ones of my own generation. And the older directors were grateful to talk with someone who actually knew their work. I think they were depressed at how little most people knew of what they had done. “What have you done for us lately?” unfortunately is a common attitude in Hollywood. But I and other cinephiles were coming along who actually were familiar with their films, and they were thrilled. I am thinking, for example, of Hawks and Stevens.

To quote Lina Lamont in Singin’ in the Rain, it meant that “all our hard work ain’t been in vain for nothin’.” Some directors were familiar with the interviewing process, but some hadn’t been interviewed much back in the day, so it was newer for them to have to think and talk about the themes in their work. I also tried to interview directors who were contemporary but were being neglected, as Richard Lester was when I interviewed him at a time when he had fallen out of favor. The interviewing process back then was an important part of reclaiming film history and understanding the work of directors and screenwriters and others.

DP: You write about how difficult your interview with your favorite director John Ford was in 1970. You call him “dour and unruly.” It was one of your first interviews with a director, so do you think if you got to do it again knowing what to expect from him, you could have had an easier time? Did you feel that if you didn’t ask a question the second he stopped answering your previous question that the interview would be over?

JM: I was flummoxed by Ford and didn’t entirely understand why he was so difficult, though I should have anticipated it. But I became more stubborn as we continued, and I kept hammering away. Mike Wilmington later observed that I had rankled Ford by probing into sensitive areas, which was true. I later learned to be more delicate in my probing.

DP: I love when you ask Ford about John Wayne not wanting to be in a film about Custer!

JM: He joked, “Oh, that’s a lot of crap. I don’t think he’s ever heard of Custer. Where’d you get that from, Bogdanovich?” That’s like the time Bogdanovich said he was thinking of getting the Duke a book for his birthday, and Ford said, “He’s got a book.”

DP: Were you frustrated that Ford didn’t want to talk about individual movies, including The Searchers, which he recalled mostly because it made money?

JM: Sure. It was especially frustrating that he wouldn’t say much about Fort Apache, the film that made me fall in love with his work in 1967. Although I was baffled by his refusal to discuss his work, I later realized I admire him for it. Directors today all give 100 interviews telling you what to think about their new films, but Ford refused to play that game. He respected the audience enough to make us want to think for ourselves.

DP: When he told you that he didn’t want to talk about his films because everyone asked him the same questions you were asking, did you believe him?

JM: Yes, indeed. It was one of the times he seemed to be giving me a straight answer.

DP: It is hard not to feel your disappointment in the character of Frank Capra, one of your biographical subjects—“my debunking biography.” You exposed his secret informing during the blacklist era but you are quick to say, “I am still an admirer of Capra’s films. Indeed, now that I understand him more thoroughly, I can understand and appreciate his films more, while identifying their flaws and contradictions more precisely.” Talk about this and how we so often have put aside our own views to appreciate films made by filmmakers who we totally disagree with politically.

JM: That’s a big subject, especially right now in the wake of Harvey Weinstein. You could write a book about it. I will just say I believe one can, in almost all cases, appreciate a work of art even if the maker is a jerk or even a criminal. If we don’t do so, there would be little art left to appreciate, since most artists are troubled people. And we shouldn’t just watch or read works that echo our political views, any more than we should just read news stories that do so. That said, I drew the line for a long time at watching John Landis films because of the deaths of the three actors in the Twilight Zone crash—one of the causes of my terminal disgust with Hollywood—but I finally paroled him after he had served 25 years in my movie jail and because I wanted to see his movie on Don Rickles.

DP: When at Variety, you were lucky enough to go on the set for Family Plot. Do you now think, “Wow, I got to watch Alfred Hitchcock direct!”? I think the big news is that you saw improvisation! As you write, “I caught him in the act.”

JM: Yes, I stood next to him and his cameraman as Hitchcock excitedly improvised a sequence that he originally had planned to shoot more simply. I wrote down every word he said. Bill Krohn told me that inspired him to write his excellent book Hitchcock at Work. Bill studied Hitchcock’s papers at the Academy library and found that contrary to his myth, he storyboarded action and special effects sequences but not dialogue sequences. Like most directors, Hitchcock would decide on the blocking and the shots for dialogue sequences while he was on the set with the actors.

DP: What director over the years was most impressive on a set? Who was surprisingly dull and noncreative? Did you ever see François Truffaut direct?

JM: I wish I had seen Truffaut direct, although I would often see him when he came to Hollywood, and one of the interviews I did with him (along with Todd McCarthy) is in Two Cheers, on Small Change. Truffaut told me if he had known I had a daughter, he would have cast her in Small Change. I was disappointed to watch George Cukor direct, though I greatly admire him, because he spoke so quietly to his actresses on his last film, Rich and Famous, as was his discreet habit. I could not hear anything except him telling them to “Speed it up, ladies,” one of his favorite directions. Cukor was a marvelous interview subject, though—bright, witty, insightful, and profane. Every director works differently, and often moviemaking can be dull to watch, especially when the lighting is being set up. I spent five hours standing on the set of The Blues Brothers, and nothing happened, no one even showed up. They were probably snorting coke in their trailers. So I left without doing a story.

Who was most exciting to watch? Billy Wilder, one of my heroes, was fascinating and entertaining when I watched him shoot The Front Page; I cover that day in close detail in Two Cheers. And Orson Welles. He was always trying something new, making up brilliant ideas as he went along, and he regaled the cast with funny stories and songs even while he drove the young crew really hard. It was a constant circus and drama and schooling to watch Welles at work.

DP: You introduce your interview with Richard Lester in London in 1973 by saying glowingly that he was “perhaps the most forthcoming, introspective, and charming director I interviewed.” You also write: “Today our interview seems tinged with a melancholy I barely sensed at the time.” I felt the same way reading it. First thought: Perhaps more directors would reveal their sadness, disappointment, frustrations and insecurities if they too were introspective. Second thought: It is almost heartbreaking that he didn’t understand the impact of his films on his appreciative fans—he didn’t even realize the enduring greatness and tremendous cultural significance of A Hard Day’s Night. I am also a fan of The Knack, How I Won the War, Petulia, the underrated The Three Musketeers, Superman II, Juggernaut, Robin and Marian, and parts of Help!. Yet, he tells you that his debut movie, The Running, Jumping and Standing Still Film is “the only film that I can say I don’t feel too embarrassed by.” What are your thoughts about how he underestimated his career? Did he have guilt for trying to make popular movies? And what do you think is his legacy?

JM: I miss Richard Lester. I sent him a copy of Two Cheers for Hollywood, and he told me although he had given most of his papers to the British Film Institute, he had kept a copy of the issue of Sight and Sound in which our interview appeared in 1973. I was touched by that. Yes, I found him extremely self-critical, perhaps dismayingly so, but he is such a serious and modest man, which I found appealing. He never seemed satisfied with his work—few directors actually are—and he retired for a number of personal reasons, including the death of one of his favorite actors, Roy Kinnear, as a result of a stunt in a film they made together. I wish Lester were still making films. We need him around, with his blend of zany comedy and biting social satire. The Bed Sitting Room is an amazing film that holds up well today as a surreal comedy about a post-nuclear world, but it hurt his career at the time. I interviewed him in the wake of that, when he was having to change to more mainstream fare. His work from The Three Musketeers onward is uneven, but has some high points, such as the lovely, autumnal Robin and Marian.

DP: Why do you say that among modern directors, Truffaut and Steven Spielberg were the ones “for whom I feel the closest emotional affinity”?

JM: There are many themes and obsessions in their lives and work I share. Truffaut was a school dropout who spent time in a mental institution; Spielberg escaped suburbia and had family troubles. Truffaut was fascinated with obsessive love stories; Spielberg is obsessed with dysfunctional families and the search for father figures. I could go on and on. They share some similar stylistic approaches as well, including lyricism and a tendency to cut to close shots unexpectedly for an emotional frisson.

DP: Do you ever think about the types of films Truffaut would have made in the 33 years since he died at the age of 52?

JM: I have been heartbroken since that day. I saved his last film to watch for years because I figured when I finally watched it, he really would be dead. But I felt he died in what would usually be the “middle period” of an artist’s career, often a less creative time than the early or late years. The Green Room (1978) was a powerful exception—but it alarmed me with its morbidity, which made me sense that something was wrong with his health before Jeanne Moreau told me in the spring of 1984 that he was dying and that “He looks like an Auschwitz victim.” If he had survived, he no doubt would have gone on to make profound films in his later years, as he had made in his youth.

DP: The 400 Blows still is beloved, more so I think than Jules and Jim, but do you sense as I do that Truffaut isn’t as admired as he once was—we revered him—and young fans don’t seek out his films as much as they should? Was he someone, like Preston Sturges and Hal Ashby, perhaps, who made great films that fit perfectly into an era—the right time—and then died as film changed?

JM: So many great directors are ignored now. It’s part of our job to re-introduce them to new audiences. I enjoy doing that with my students at San Francisco State. Most are stunned to see classic films they didn’t know—such as Lubitsch or Ozu films—and to realize how good they are and how directly they speak to people today.

DP: I really appreciate your (and Patrick McGilligan’s) interview with George Stevens because it includes interesting nuggets that make me want to see his films again, all together. That should make you happy because you lament that “Few American directors’ work has suffered such an eclipse of reputation as that of the late George Stevens.”

JM: Sight & Sound’s generally good review of Two Cheers mocks me for writing that Stevens is “the most underrated American director today.” I am convinced I am right, so I don’t mind the knock. I like his early comedies, but I don’t share the kneejerk conventional wisdom today that he declined after he came back from the World War II with PTSD and depression and made more solemn fare (which was celebrated in its time, a drawback to his acceptance today). I think A Place in the Sun and Shane are masterpieces. For a Ford aficionado to say Shane is the greatest Western ever made seems heretical, but that’s my belief, since it is deliberately and perfectly archetypal. I admired The Diary of Anne Frank when I was 12 but was afraid to see it again until recently because I feared it would be so lugubrious and claustrophobic. To my relief it is still gripping, and of course it isclaustrophobic, but I found that part of its personal quality was that Stevens, who had filmed the war and the concentration camps, managed to combine the Holocaust with a genre he had worked in so memorably before the war, the romantic comedy. I tried for a while to raise interest in a biography of Stevens but found no takers. I liked him very much as a man as well as a filmmaker. He was humane, sensitive, warm and hearty in his humor.

DP: Another director who has lost a bit of his luster since the 1960s is George Cukor, so I really liked your tribute to him and long interview (with Todd McCarthy) with him in your book that focuses on his later work. I’d like you to discuss something you wrote about Cukor: “With his non-doctrinaire, instinctively feminist sensibility, Cukor usually filmed from the viewpoint of his female protagonist.” I fear that back in the sixties and seventies we were all guilty of stating that Cukor had so many complex, interesting female leads because he was gay, when the truth was that he was a male who had a feminist sensibility. The subject of one of your chapters, James Whale, was also gay, but, with an exception or two like Show Boat, was much more interested in his male characters.

JM: Gay directors can’t be characterized homogenously any more than straight directors can. Whale’s work deals more explicitly with outsiders, often by employing the horror genre; Cukor’s has more range, and he always pointed out that the men in his movies are important too, as indeed they are. Cukor and Whale were very different in their approach to their work and their lives. Whale’s career evidently suffered because he was more defiantly “out,” while Cukor was discreet even though his homosexuality was an open secret in Hollywood. Whale was a more stubbornly independent man who didn’t rebound as well as Cukor from setbacks with the studios, so he retired early while Cukor soldiered on. My favorite moment with Cukor was when I was asking him, during an interview at the Beverly Hills Hotel Polo Lounge, what it felt like to be fired from a movie. He put his hand on my arm and said to his publicist, “Notice with what finesse he avoids mentioning the title Gone With the Wind” (actually I was thinking of another movie). Cukor is a great director, and I found him a lovable man, but I never quite got a handle on how to analyze his work. It’s frustrating, but maybe some day I will figure out how.

DP: Talk about your relationship with John Huston.

JM: I came to know Huston fairly well—though he was an enigmatic man—by co-writing The American Film Institute Salute to John Huston (for which I and my writing partner George Stevens Jr. won Writers Guild of America awards), interviewing him, and acting with him in Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, all of which deepened my interest in Huston’s work. I passed on an offer to write a Huston biography, though, partly because I wasn’t interested enough but mostly because it was pitched as an authorized biography with his children having veto power, and I don’t write those because they would take away your independence.

DP: When Huston and Welles got together, who would do most of the talking?

JM: I wasn’t privy to their discussions much on the set of The Other Side of the Wind, since they tended to talk more in private. Welles was voluble, while Huston tended to be more introspective. I sat next to him for a couple of hours once while waiting to shoot, and he hardly said anything, just puffed on his cigar. One of my favorite moments, though, was when Huston’s director character, Jake Hannaford, entered the party with a blonde teenaged companion in tow and gave her a lecherous look. I could tell it was too much. I wondered how Welles would handle this with a crowd watching, since Huston was his peer. Welles thought for a moment and said, “John, do you know who you remind me of in this scene? Your father.” Huston beamed, as he did whenever his father, the great actor Walter Huston, was mentioned. He said, “Oh, really Orson? Why?” Welles said, “Because he had that kindly, paternal air—but nobody ever had a higher score.” They both roared with laughter, and Huston did the scene again with a sly little smile that gave an ironic tone with “that kindly, paternal air.”

DP: Did you ever think of teaching a course on Huston? You could explore the question you ask: “Who is John Huston?”

JM: It’s high time for me to teach a course on Huston. His work is so rich and diverse. I’m surprised I haven’t gotten around to it yet. But I teach his films in my beginning screenwriting class—I show The Man Who Would Be King and The Deadafter having the students read the great stories by Kipling and Joyce that they are based on, and it helps illuminate the process of adaptation. As I write in an essay in Two Cheers, and mentioned to you before, I believe Huston is the filmmaker who does the best literary adaptations, often of works considered virtually impossible to film, and yet he makes the stories his own while channeling their authors.

I use adaptation as the basis for my course, since it gives the students a good story to work with while they are learning the screenwriting craft. I center my 2012 book Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless on that topic. I also show Huston’s great World War II documentary Let There Be Light to my screenwriting students, since I have them write scripts based on short stories about PTSD. I helped liberate Let There Be Light from being banned by the U.S. government and write about that saga and the making of the film in Two Cheers.

DP: We all like to champion unfairly neglected films by directors who made many masterpieces. For instance, you rave about Elia Kazan’s Wild River. I’m sure you have found many of us who agree with you. But I’m not sure how many people have told you, “At last, someone else who thinks Billy Wilder’s Kiss Me, Stupid is ‘glorious!’”

JM: I just discovered that Truffaut liked it very much! I have found several other “deviated preverts” (to quote the twisted line from Dr. Strangelove) who admire the Wilder film as well. I write in Two Cheers that Kiss Me, Stupid “was so far ahead of its time in satirizing American sexual hypocrisy.” I adore the characters, who are deeply human and moving in their foolishness, and am entranced by how the outrageous situation is filmed with such visual elegance and verbal wit. Joan Didion was the film’s only critical champion at the time. She wrote that Wilder “is not a funnyman but a moralist, a recorder of human venality. . . . The Wilder world is one seen at dawn through a hangover, a world of cheap double entendre and stale smoke and drinks in which the ice has melted: the true country of despair.” After reading that piece, which was published in Vogue, Wilder wrote her a note: “I read your piece in the beauty parlor while sitting under the hair dryer, and it sure did the old pornographer’s heart good. Cheers, Billy Wilder.”

McBride with Truffaut, Fuller and McCarthy, 1975 (from Two Cheers for Hollywood)

DP: I believe you and I have similar tastes, so I was surprised by your hostility toward one of my favorites, Rebel Without a Cause, even lumping it with Easy Rider because its hero’s naiveté “is somehow a sign of moral superiority over the cynics and cretins who make up the rest of the cast.” I would have thought you as a kid could have related to Dean’s misunderstood, frustrated, isolated teenager who has trouble at home and at school, and appreciated that this was the one film about teenagers in the fifties that completely sides with them rather than adults. I find it the most emotional of all movies of that era and that it never takes the moral high ground. And there were certainly more cretins in Westerns, even before Peckinpah and Leone. I can see how Sam Fuller wouldn’t like Rebel because he didn’t care about teenagers, but not you!

JM: I don’t like sentimental films about teenage life, and Nicholas Ray was always sentimental to a fault about outsiders. Our film-buff cronies back in the day worshipped him for that and because he was destroying himself, which I don’t think is romantic, either. I prefer more hard-edged, painful stories about teenage years, which are horrendous for many people and were in my case. I also don’t like how Ray makes the parents seem like buffoons; it detracts from the seriousness of the story. My book The Broken Places is in many ways an antithesis to Rebel Without a Cause. And in Rock ’n’ Roll High School—a comedy, unlike Rebel—I followed Sam Arkoff’s advice for teenage movies—not to show the parents. A gaggle of parents appear only briefly on the lawn of the school during the record-burning, and Kate’s mother is heard on the phone (wonderfully played as clueless by New World story editor Frances Doel), and that’s it.

DP: How close did you get with all the young filmmakers who worked with Roger Corman and then made films on their own?

JM: I remain friends with Joe Dante, who directed parts of Rock ’n’ Roll High School and gets joint story credit with Arkush. I think Joe is the most brilliant of that group. He’s somewhat underrated today and has to scramble to cobble projects together. It’s a sign of how decadent the industry is that it can’t give Dante more work and doesn’t fully recognize his great talent.

DP: What was it that made you such an admirer of Steven Spielberg from the start?

JM: When I saw his 1972 TV movie Something Evil, I was immediately aware of his great visual imagination. I already had read of him in Variety and knew how unusually young he was; Hollywood was still dominated by old timers then. I had thought of calling Spielberg for an interview when I went to Hollywood in 1971 to do more shooting on The Other Side of the Wind, but I didn’t get time. I began thinking of writing a Spielberg biography in 1982, because he was grossly underrated and maligned by most critics and authors, but I thought he was still too young for a biography. I finally decided to do it once he decided to make Schindler’s List, a decisive step in his creative and personal evolution, even though he had made “serious, adult” films from the beginning of his career, such as the “Par for the Course” episode of The Psychiatrist, Duel, and The Sugarland Express. And some of his amateur films dealt with serious subjects. Billy Wilder said that Spielberg was a great director when he was 10.

DP: At the beginning, would you have predicted he’d make historical films such as

Schindler’s List,

The Color Purple,

Amistad,

Saving Private Ryan and

Lincoln?

JM: I still wonder to some extent where he gets that impulse from, other than from his lifelong interest in World War II (which could be seen in his amateur films) and the Holocaust (he spent his first years in a Jewish neighborhood in Cincinnati with many survivors, and some of his family were killed in the Shoah). What surprises me about his great interest in history is that he was not a good student; he is dyslexic. He has people helping him with research and usually has good screenwriters. Not all his historical films are equally accurate, but generally he places a high value on accuracy. And he has a way of bringing history to life in vivid and complex ways for a popular audience, as John Ford did. The scene of Lee surrendering to Grant in Lincoln is filmed shot-for-shot the way Ford would have done it. One reason I admire Spielberg is that he has used his success in positive ways and not let it throw him, as happened to Frank Capra. And Spielberg wisely alternates his more dramatic work with his so-called “entertainments,” as Graham Greene used to do.

DP: You wrote that Spielberg wanted popular success at the beginning of his career “partly because of his deep-seated personal need for social acceptance.” Could it be that he also wanted validation as someone like his idol Alfred Hitchcock, whom he called “The Master,” could make good films that made money? And could it be said that he made more serious films later in his career because he had a deep-seated personal need for critical acceptance?

JM: Well, as I said, he made “serious, adult” films early on. But you are right that he has always had a need for acceptance. I don’t agree with his detractors who claim he is driven mostly by greed. Other than wanting commercial success to ensure him creative independence, which is laudable, Spielberg is not driven by money. The more he was denied acclaim by reviewers and his peers, the more he wanted it. He wept when he won the directing Oscar for Schindler’s List. I wish he hadn’t done that, because it’s only an Oscar, but I understand why, particularly after the way he was harshly snubbed by the Academy for making The Color Purple; he is always especially attacked when he makes films about black people.

In his later years he is more driven by pure creative passion than by a need for more acclaim, though the need for acceptance will continue to be part of what drives him. His outsider status as a youth was and is a major motivating force in his life. Being persecuted by anti-Semites was part of that, and some of the tropes used against him by his detractors (such as the claims that he is greedy, “manipulative,” vulgar, a propagandist, a bad influence on children, etc.) are familiar anti-Semitic smears. I discuss this in the third edition of my Spielberg biography and examine there and in Two Cheers why some people still hate him so much.

DP: What filmmakers besides Spielberg have come along since the seventies who have excited you the way the great filmmakers from the twenties to the sixties once did?

JM: The Coen Bros. are great filmmakers, our closest contemporary equivalents to Billy Wilder, though they have a way to go before they can rival him. I have long felt they are misunderstood and underrated, for a variety of reasons, including their unpredictability and the remarkably diversity of their work. So I wrote my monograph on them for Two Cheers, after watching all their films again in a two-week period, deliberately out of order, so I could reevaluate them in fresh ways.

DP: I’d think they would be hard to write about because almost every film goes in a new direction and there has to be a new evaluation, and what you wrote is already dated. And, as you write, they never explain their works.

JM: It’s good sometimes to analyze an artist or artists in mid-career, as I have also done with Spielberg. You hope to be surprised by their future development. I am sure the Coens will continue to evolve in ways we haven’t expected. That is a sign of true artists.

DP: I find it interesting that different people have different favorite Coen Bros. films, and think some of their films are minor that others think are masterpieces. For instance: My favorite Coen Bros. film is Miller’s Crossing and you call it “pretentious.” (You also call it “grim,” but I’m not sure that is criticism.)

JM: My views on some of their films changed when I re-saw them. I liked

Miller’s Crossing when I first saw it, but now find it dismal in every way, as I do

The Hudsucker Proxy. I don’t like

Intolerable Cruelty as much as I once did. But I like

Fargo a lot more than I did at first, when I didn’t appreciate their mockery of Midwesterners, until I found that my relatives in Wisconsin love the film because it captures their way of speaking and cultural ethos so perfectly. The Coens are from Minnesota, after all.

Fargo is perhaps their most seamless mixture of comedy and violence, and it has the most endearing performance in their work, Frances McDormand’s complex and humane portrayal of the pregnant police chief.

The Big Lebowski is also wonderful, as is Jeff Bridges in it. The film of theirs I found hardest to come to terms with is

A Serious Man, though it’s fascinating in its existential bleakness; my reactions to it oscillate to some extent.

Burn After Reading, which was neglected by reviewers, seems better every time, as does

Inside Llewyn Davis.I think it’s a sign of the Coens’ artistry and originality that our views of their work evolve as they do. Maybe I will revisit that monograph in a few years to see how my views have changed again.

DP: I tell people that to fully appreciate the Coen Bros. they should take note that their films take place in an alternate—often a movie—universe. Would you tell them that?

JM: Sure, because they are postmodernists with an advanced taste for parody. I usually don’t like postmodernism, but they practice it in such a skillful and witty way, visually and verbally, that I am enthralled by their style.

DP: Do you think the cult status of The Big Lebowski is partly because it’s a Coen Bros. film, or don’t fans care who made it? And why do you think it’s such a phenomenon?

JM: It’s a stoner Bible. And it’s simply a great film. I can’t imagine why anyone wouldn’t like it. It’s a tribute to Raymond Chandler in an ingenious modern way. The Coens have tried to alert people that they are more influenced by writers than by filmmakers. The other writers they mention as role models are Flannery O’Connor and Dashiell Hammett.

DP: Talk about the contrast between Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne on the set of The Shootist. Did you feel you were watching film history on that set? Is it more special in retrospect because that was Wayne’s last film?

JM: One young crew member told me, “There’s so much respect generated around here, the crew is just walking on eggs.” Wayne was much more extroverted than Stewart, who sat quietly in his chair (partly because of his deafness) while Wayne made jokes with the crew. Yes, there was a sense of things ending. The scene I watched them shoot for two days was the one in which the doctor played by Stewart tells the gunfighter played by Wayne that he is dying of cancer. It was one of my great experiences to watch my two favorite actors work together. They mostly conferred on timing and technical points like the consummate pros they were. Director Don Siegel had his clashes with Wayne, but he would say, “Action, please.” Siegel told me, “I’ve directed a lot of stars—even before I was a director, I had Bogart, Cagney, and all the rest when I was doing montage scenes at Warner Bros.—but for the first time in my life I’m conscious of working with a legend. I can’t help feeling a bit in awe of the man, but at the same time I can’t let it throw me, because you’ve got to be able to have disagreements.” Siegel added kiddingly, “He eats directors for breakfast, but when he eats me he’ll get indigestion.”

DP: Wayne told you that it would have been impossible for him to play himself onscreen, which his detractors always said he did. Were you surprised he thought about such criticism or was it so prevalent that he couldn’t ignore it?

JM: He seemed surprisingly sensitive to criticism. When I asked if John Ford did some second-unit work on Hondo, a film Wayne’s company produced and John Farrow directed, Wayne said, “Jesus Christ, don’t you people ever give me credit for anything?” I understand his feelings, because Wayne has been so mistreated by most critics and many film historians, whose lack of understanding of what constitutes good film acting causes them to dismiss him for allegedly just “playing himself.” As Wayne thoughtfully told me, “It is quite obvious it can’t be done. If you are yourself, you’ll be the dullest son of a bitch in the world onscreen. You have to act yourself, you have to project something—a personality. Perhaps I have projected something closer to my personality than other actors have. I have very few tricks. Oh, I’ll stop in the middle of a sentence so they’ll keep looking at me, and I don’t stop at the end, so they don’t look away, but that’s about the only trick I have.”

DP: John Wayne is, along with Stewart, my favorite actor of the sound era, so I understand why you call him your favorite actor. But is it hard to explain to others, especially those who don’t like Westerns?

JM: It’s a struggle because of the misunderstanding about the nature of film acting I just mentioned and because too many people let Wayne’s reprehensible politics affect their judgment of his work. I am tired of arguing about his talent, which should be self-evident, but I wrote an appreciation of him that’s in Two Cheers in which I grapple with most of these questions, so I will refer people to that! But if people don’t like Westerns, that’s another issue—of lamentable myopia.

McBride and Grady Sutton in “Rock ‘n’ Roll High School,” Photo: New World Pictures, 1979

DP: It’s interesting that the word Jimmy Stewart used most when describing his screen image was “vulnerable.” It makes sense but I never thought of that word—I think he equated “being vulnerable” with when his strong, good guys “went dark.” What do you think?

JM: Vulnerability stems from anxiety and vice versa, and many of Stewart’s roles are filled with both, even before he went to war. I worked with him several times and often talked with him but never managed to understand him very well, since he was so reticent and inarticulate, even though he went to Princeton. When I would ask about his experiences as a bomber pilot in World War II, he couldn’t or wouldn’t talk about them. Capra told me that on It’s a Wonderful Life Stewart said he wanted to quit acting because it wasn’t a “decent” job for a man. So Capra asked Lionel Barrymore to give him a pep talk. Barrymore said, “Do you think it’s more decent to drop bombs on people?” Capra said that was “pretty rough” but that it did the job. Stewart admitted to me that he came back a somewhat different man, and his postwar career in films for Anthony Mann, Hitchcock, Ford, and others contains many brave and disturbing roles in which Stewart shows great vulnerability.

DP: You interviewed Peter O’Toole at the time he was “a bit frantically overpraising his newest film, Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man,” and describe him as “such a magnificent ruin.” Would you have liked to have interviewed him when he starred in Lawrence of Arabia instead or, looking back, was 1981 the ideal time?

JM: I borrowed that “magnificent ruin” phrase from what Orson Welles said to me about Edmond O’Brien when we were doing The Other Side of the Wind, to kindly explain why he was taking away some dialogue I was having trouble understanding and giving it to Eddie, who did it wonderfully. Any time would have been a great time to interview Peter O’Toole, the modern actor I like most. He was so witty and smart and incandescent. He gave me a marvelous interview while laid up with a cold in his bed in the Beverly Hills Hotel, imitating Garbo in her death scene in Camille. I am glad we had such a rapport, because I was a fan of his from the earliest days of his film career, especially in What’s New, Pussycat?, a film that helped shape me as a young man.

DP: Did you ever interview your favorite actress, Jean Arthur?

JM: I was fortunate to spend a lot of time with her in the 1980s at her home in Carmel, thanks to an introduction by Frank Capra. I was one of only a handful of people she would see in her later years, and we had a lot of fun talking.

Life magazine once wrote that she was so reclusive she made Garbo look like a party girl. She told me some revealing things, such as when I asked why she left Hollywood. She said that when she was under contract to Columbia in 1945, the female stars’ dressing rooms were in a row, with a dark hallway connecting them. There was a secret entrance, and studio chief Harry Cohn would come in there and attack the actresses. Jean decided to kill Harry Cohn. She thought she could shoot him in the hallway and get away with it. But she told me that instead she walked the backlot for three hours and decided to quit the business instead. She left Columbia for the theater and made only two more films,

A Foreign Affair for Billy Wilder and

Shane for George Stevens, plus her short-lived TV series.

Sexual harassment and assault in Hollywood did not begin with Harvey Weinstein; it’s always been an odious part of the movie business.

DP: You write that your 1970 interview “with the much-maligned African American comic actor Stepin Fetchit is one of the most influential pieces I’ve published, which pleases me because he was so mistreated by Hollywood and by film historians.” Tell me about the importance of your interview then—and now.

JM: Not only was Stepin Fetchit a major cultural figure who managed to become the only male star in 1930s Hollywood—he told me Hollywood was “more segregated than Georgia under the skin,” which unfortunately is still true today—but he was a brilliant comedian whose work can be viewed as subversive of racial stereotyping. You have to be as hip as John Ford to get what Stepin Fetchit is doing. Most people can’t see the artist behind the mask. But watch him in Ford’s Judge Priest and The Sun Shines Bright to see trenchant commentary on Jim Crow. I interviewed Stepin Fetchit in the basement of a strip joint in Madison. He was at the lowest rung of show business, unfairly ridiculed and despised, and I wanted to give him his voice again. I am pleased that the interview we did (“Stepin Fetchit Talks Back”) has been influential on two sympathetic biographies of the man.

DP: I love Stepin Fetchit, so I’m pleased you defend his controversial screen portrayals for all of us fans by saying “that his art consisted precisely in mocking and caricaturing the white man’s vision of the black: his sly contortions, his surly and exaggerated subservience, can now be seen as a secret weapon in the long racial struggle.” I would think this gut-feeling argument of yours is very difficult to defend, and that’s why you added a line: “But whatever one makes of Stepin Fetchit’s work, he was one of the few nonwhites to achieve status in American films, and he deserves to be remembered.”

JM: In fact, as I reveal in Two Cheers, those eloquent words of introduction to the interview were written by the late Albert Johnson, not me. He was a respected film critic and festival organizer. I was grateful to Film Quarterly, a leftist journal, for running that interview with such a controversial figure, but they wanted an African American writer to validate the subject, so they asked Mr. Johnson, which was OK with me. He didn’t take credit for the introduction at the time, but I wanted to give him credit in retrospect in my collection. I love his words about Stepin Fetchit. I don’t think they are difficult to defend: they sum up the essence of his art.

DP: I’m glad he opened up to you and spoke about his relationships with the most militant black athletes ever, Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali.