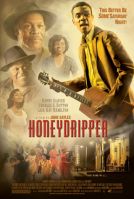

Sayles and Renzi Present "Honeydripper"

(from brinkzine.com 12/27/07)

John Sayles

John Sayles

As 2007 comes to an end, and Hollywood unleashes its blockbusters and we're drowned by a gigantic wave of crass commercialism, it's refreshing to see the release of a new film by indie icon John Sayles, a rare figure in the cinema world whose integrity has been unwavering. "Honeydripper" is the sixteenth film written and directed by Sayles, and the thirteen produced by his long-time companion Maggie Renzi, and as with such gems as "Return of the Secaucus Seven," "Lianna," "The Brother from Another Planet," "Matewan," "Passion Fish," "Limbo," "Lone Star," and "Sunshine State," its riches far exceed its budget for the simple reason that the two filmmakers, their crew, and their actors really care about the story they are telling. "Honeydripper" is set in a small town in Alabama in 1950. One-time musician Tyrone Purvis (Danny Glover, leading a super, almost all African-American cast) is in danger of losing his juke joint, the Honeydripper Lounge, so he sends for blues legend "Guitar Sam" to attract a young crowd to a one-night-only performance. A polite young guitarist named Sonny (played by rising Austin blues guitarist, Gary Clark Jr.) comes to town and takes a fancy to Tyrone's pretty stepdaughter China Doll (model Yaya DaCosta). He might be able to save the day if Guitar Sam doesn't show, but the white sheriff (Stacy Keach) tosses him in jail for vagrancy and forces him to work in the cotton fields. Will Tyrone swallow his pride and make a deal with the sheriff to free Sonny? A mix of music and social history, "Honeydripper" opens Friday and I assure you it's like nothing else in town. I took part in the following roundtable interview with Sayles and Renzi last week. I note the questions I asked.

Danny Peary: While watching the beginning of "Honeydripper," I was thinking it is similar to a play, with the juke joint, the Honeydripper Lounge, as the main set every character spends time in. But by the end I was thinking of it being like a short story, maybe because of the unresolved storylines and with Sonny coming through town and the juke joint and glimpsing the situation there. Did you write the film thinking of it that way?

John Sayles: "Honeydripper" was not based on but was inspired by a story in my last short story collection, "Dillinger in Hollywood." That short story is called "Keeping Time," and it's about a forty-year old drummer in a band of twenty-year-olds. And he's wondering, "What am I doing here? Am I boring these kids? Or are they boring me?" Then this janitor comes over and says, "I used to be Guitar Sam." He's an eighty-year-old with arthritis who talks about how he once played guitar. In "Honeydripper," Charles Dutton's character Maceo says, "I wish I'd been there just to here the cat play." Well, when I finished my story there was this little nagging thing telling me that there was a whole other story in that guy back in the day.

DP: What is the story of Tyrone "Pine Top" Purvis?

JS: He's over fifty and has grown up with the music. He was there at every point: As a kid he was there when the blues started being played; he experienced New Orleans jazz; he was in the swing bands; he's been in the jump bands. And now there's this rhythm and blues thing which he can kind of hang with but does he want to take the next jump into something he doesn't quite understand and doesn't know if he likes to play. What was that turning point like for the musicians like Purvis when they must have realized—just like people in Hollywood realized when the talkies began—that the train was leaving the station and it's time to jump on board or be left behind. He is ambivalent. "Do I really want to go there?"

He's a character I've never seen before, but I met guys who talked about men like him. They were African American men who in 1950 in the South somehow managed to be their own men. It was scary sometimes and they had to be on their toes the whole time and be good politicians in some ways, but they also had to carry themselves—and it's one of the reasons we were so happy when Danny Glover said yes—with this thing of "Don't mess with me." In his club you don't fight, and that's understood by anyone who knows him in this town. It helps that he's backed up by Maceo, who has a different personality.

DP: We like Tyrone and Maceo, but they're not pure. They survive day to day, and even are willing to do underhanded things to make enough money to keep going.

JS: And Tyrone has to do a terrible thing, which is to dip into his step-daughter's money.

Q: This film deals with African American culture. How do you get into the head of the black man, as when Tyrone's wife Delilah (Lisa Gay Hamilton) asks him why he doesn't quit?

JS: I think the main thing I try to do as a writer is listen and not be judgmental. I've lived in this country my whole life; I grew up in a very interracial city and went to interracial schools. And I discovered that if you listen, without thinking you know the end of the story, eventually you accumulate stuff. Also I've read autobiographies of half a dozen blues musicians, I've heard their interviews, I've talked to some of them personally. So eventually you build up what you know and understand. It would be harder for me to set this movie in Jamaica because it's not my culture. But our culture is made up of a lot of subcultures and I've been around it my whole life and I can get inside in a certain way. Then I basically have a failsafe, which is to change something that is wrong. I usually change about three lines per movie. Sometimes it's just a tongue-twister that the actor can't say so I rephrase it, but usually it's when an actor, because I've given him a character bio and discussed the character with him beforehand, will say, "I'm not sure my character would say it this way." There was a line in "Passion Fish" when Alfre Woodward and Angela Bassett are in a kitchen. They're both from Chicago, one is now a famous soap opera actress, the other is working as a maid for this woman who is paralyzed. They talk and realize they've switched positions. One started middle class and is downwardly mobile and the other grew up in the Cabrini-Green projects. Alfre had this line, "Oh, that's a long way up." And they both came to me and said, "You know, unless she's really trying to diss her, she might not say that." We talked about it and we finally changed it to "That's a long way out." That's the kind of thing I rely on from my Hispanic actors, from my old actors, from my female actors, from anybody who comes from a place I don't. You try to have the conversation be open enough so that they will tell me what their character wouldn't say.

Maggie Renzi: It's a long history for John of writing about mostly Americans—though there were two movies set in Mexico and one in Ireland. Think of the black characters in "The Brother from Another Planet," " City of Hope," "Passion Fish" and on and on. I met a guy from the NAACP when I was out in L.A., and I said, "It's time for an Image award for this guy." People have mentioned this before. We were with Danny Glover in Greece at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, where they had a complete restrospective of our movies and it was awesome. Danny's friend was there. She is an African American woman about his age and she kept looking at John and finally said, "You? You wrote the whole thing?"

JS: With "Honeydripper," I want the audience to meet a community and get the feeling there's more to it and want to get to know more or the people. Within the African American community, there are class differences, relgious differences, age differences, differences of opinion--there's a whole world there. And there's a white world that they bump into every once in awhile. That's a ceiling. To me the heaviest line in the whole movie is when the sheriff says, "Take your hat off." I'm old enough to remember that in South, if a black man was talking to a white man you took your hat off or were told to; or you were considered impudent. That's a pretty heavy thing to live with. It's something I kind of throw away in the movie, but it had to be there.

DP: It's dramatic and a bit startling when the sheriff takes off his hat for Tyrone's wife Delilah.

JS: That was something Stacy Keach did and I told him to keep doing it. Because there's a part of him that's courtly and Southern and there's a part of him that's kind of amused by these people. Because Tryone pushes back, he has a lot more respect for him than he has for a kid like Sonny who he meets on the road and can just toss in jail.

MR: He also would go a mile for fried chicken like Delilah makes. That's such a funny thing about him.

Q: You seem to avoid stereotypes.

MR: I find it interesting to talk about stereotypes because we have read the word "stereotype" and I want to say that the writers are white. I want to say, "Have you ever been south of the Mason-Dixon Line, darlin'?"

Q: You talked about the music—obviously it plays an enormous part in the movie's black community and culture.

JS: That's why there is both the revival tent and the juke joint. The people were getting nothing for picking cotton. Those bags weighed fifteen pounds, and they were picking two hundred and fifty pounds a day and getting about $2.15 at the end of the day. It was a big deal to have cash because the rest of the time they were in barter or stayed in debt to the company store. If you do that a lot of your life, then Saturday night and Sunday were you chances to transcend that. And that was mostly through the music, blues and gospel. So you go to the juke joint or church or both. A lot somehow managed to do both, although on Sunday they heard they were too wild on Saturday night. People, especially church people, have been asking me about why Tyrone's wife Delilah is about to come over to the Lord, but instead goes back to the juke joint. And I say, the preacher says to her that the Lord is telling her where she has to be. And He does, and she goes there.

In both places music was transcendent for the people. The blues was the way to tell your story. You weren't going to be published, but you could pick up your guitar. There were a lot of blues people who really had only one or two songs. They heard other blues songs but wanted to tell their story so learned one or two simple chords. They told their story through their song and maybe somebody heard it and it became part of the vernacular. Music in this one is what wins the day. Even if it's not the next day too, it is at least that day. In the first paragraph in the bios of blues musicians, most of them say, "I didn't want to pick cotton." That was the driving factor in playing music, because they saw what picking cotton did to people around them. That legacy was so hard. The idea was, "I can jump on a freight town and go to another part of the world and not pick cotton."

DP: They were also the best at what they did, whether picking cotton or playing music.

JS: Yes. The guys who weren't too good playing music eventually ended up picking cotton again.

Q: Anyone familiar to your movies knows that music is extremely important to you as well.

JS: Yeah, it is. Certainly when I do a movie, even if it's not about music, one of the first things I do is think about the music and send music back and forth with Mason Daring, our composer. It's just amazing that human beings have this ability to create and perform music. Incidentally, Ruth Brown was originally going to play Bertha Mae but she passed while we were shooting and Dr. Mable John played her. We did have her pre-record "Things 'Bout Coming My Way".

DP: You wrote a couple of songs that are in "Honeydripper."

JS: I wrote three actually. I don't really write music, I just think up a melody and some lyrics and Mason Daring will make it into music. I've done it before. It's cheaper and it's fun and I can tailor it to the moment in the film, when it's often hard find the exact right lyric and song. Take "China Doll." How do you impress your girlfriend? You write a song about her, which Sonny does. So I channeled Buddy Holly.

Q: With "The Great Debaters" and this film, there seems to be real look back to this critical period in American history and people are trying to understand segregation in South. Was that a reason you made this film?

JS: It is an era I don't think we've looked at enough. I was born in 1950 and "Honeydripper" is set in 1950, and I spent a lot of time in the South as a kid. So it's always the place and era—and the story of its music--that interests me. Race in this country is usually represented in drama by either plantation days or the Civil Rights Movement. There were a lot of years in between. One thing people in this country don't think about is that the apartheid laws didn't start in South Africa until about 1950; most of the Jim Crow laws in the South didn't start in each state until well after the Civil War. Then each state started taking away rights from African Americans. North Carolina was the last, and that was about 1898. We had African American representatives in Congress for many years, then they disappeared for fifty years. That's not part of our history that we talk about. I feel that in America it's too easy for us to feel like we were born yesterday. We we don't want to know that old stuff, we start from scratch. Well, we don't start from scratch. We're born into a world with certain suppositions and culture and ideas that we don't even realize we've been ingrained with. One of the interesting things about historical movies is that you can remind people. Just like it is with rock 'n' roll. There was a lot of rock 'n' roll around before they called it rock 'n' roll. The Civil Rights Movment was going for a long time before they called it the Civil Rights Movement. A lot of people sacrificed a lot and risked a lot to just to bang their heads against that wall.

Q: Surely one of the challenges of this film was to get the period right and make it feel right within the framework of a small budget.

JS.: This was a very ambitious to film to make in just five weeks, especially since Danny Glover was available for only three and a half weeks. So you hire a lot of really good people, you do a lot of scouting and find the right places to shoot. We did very careful location work. The town you see with the railroad tracks is Georgiana, Alabama. It was where Hank Williams grew up, though we didn't know that when we picked it. When it modernized, it did it about two blocks from the main street, so we had to replace a few awnings and stuff like that but a lot of the town as it was in 1950 was still there. The army barracks you see are from World War II, and are still standing. They happen to be in Anniston, Alabama, which is one of the reasons that we shot in that state.

MR: They were four and a half hours from where we were, but it was worth the trip.

JS: They were decommissioned. It was the time of Korean War and they'd closed down most of those bases after World War II. So instead of painting all these buildings, they were chipping off the existing paint and cutting the weeds. So we said, "Please don't chip off any more paint, don't cut the weeds. We'll come there and do it on two or three buildings and then you can do what you want after we leave."

MR: We might not have been able to do it five movies ago, but by now we really know how to get good value. I remember at the end of filming "City of Hope," which we made in the eighties. We also made that in five weeks with a cast of forty-five people and about fifty locations. On the last day our DP, Bob Richardson, threw the script at John and said, "The next time you want to make a low-budget movie, you write a low-budget movie." That's what he never does. He never actually writes a low-budget movie. But this one, fully half of the shooting days were spent in the Honeydripper. So although initially it was expensive—we had to put a new floor in, we took out the ceiling, we had to repair the roof—once we'd done all that, and lit it basically like a stage, we could go in there and never move the trailers or caterers and work a full fourteen hours. So you can make really good economical decisions. I think the biggest decision we made was that it had to be beautiful. So the money went into beautiful on the screen, not into very attractive trailers for the actors. It went into taking the time to light, which a lot of low-budget movies don't do anymore. A really good DP, Dick Pope, took the time to light it and have everything on the screen be worth looking at.

Q: John, is the budget something you're conscious of when you're writing specific scenes in the script, as opposed to when you're filming the picture?

JS: I try not to write with the budget in mind, but I'm afraid I do. When I write the second draft, when I know we're going to make the movie, there is some very practical writing in there where I consider: Can we shoot this in the day rather than the night?; Can we get rid of a character? Can I consolidate something? Can this character not speak so we won't have to pay him for that? Can I set a scene on a set we already have, so we don't have to build a new set for only that scene, or travel to it? With only five weeks to make the movie, storyboarding was very important. I am always very specific about the storyboarding. I have to figure how we are going to attack each scene each day. I want discussions with my director of photography or the production designer to happen before we're on the set. When we come to the set, we know what we're going to try to do and don't waste time. We try to schedule the priorities first, so we make sure to get the most important stuff; and the stuff that would be nice to have but we can live without is filmed at the end of the morning, just before lunch, or at the end of the day. If something goes wrong, we have a Plan B and a Plan C. When they shot the first "Rocky," they painted only two sides of the ring because they didn't have the money to put the camera on the other side, too. There's a lot of that thinking in making this movie, where I'd say, "These are exactly the two angles I'm going to use, and everything else can be untouched."

MR: And the rest of it is: We're going to go into Bertha Mae's room for only that one scene around her body and we're going to see every single corner of that room. That meant that our decorator, Alice Baker, had to select so much to describe this woman's long, rich life. I was lucky because I got to go shopping with her. I’m a junker, and what fun it was to go shopping with "other people's money"—it was in fact our money, but it was money from the budget. Atlanta was closing a famous flea market, called Lakewood, that had been open for twenty-five years. And there were big, sentimental articles about it in the local papers because it had been a social meeting place for years. We went with a big carriage and just filled it, filled it, filled it. John's biographies of the characters are given to the actors but also are shared with the art department, with costume, with hair and makeup. By the time we made the movie, I knew these characters like they were real people. So I'd go shopping with Alice sometimes come back with something and say, "For Bertha Mae's bedroom, right? For Tyrone Purvis's kitchen, right?" We shopped low on the hog and really successfully. I think the costumes are a big reason this movie is so beautiful. Our costume designer was Hope Hanafin, who did "Lackawanna Blues." She's very familiar with the period and African American culture. She said to me, "I can do this on your budget, if we can use vintage clothes that I can get from the costume shop." That means you have to cast tiny extras, because anyone who shops vintage knows, people were smaller then. We got really lucky at Alabama State University, the historically black college in Montgomery that has a great theater and dance department. We made a connection there through our local casting people and a lot of those great looking kids you see in the club come from ASU.

Q: You always have had uncanny casting.

MR: I can say we are great at casting.

JS: And very lucky.

MR: On "Honeydripper," we had a wonderful casting director, John Hubbard, who is English—go figure. You know what it is about him? It's that he doesn't think he already knows, so he sees everybody. He came over to the States and he must have seen two hundred actors for the three young male cotton pickers. He sent us the resumes of about a hundred. We'd go right through them and give various reasons why they weren't right, and finally ended up meeting about twenty of them. That was a beast for us because that was an age we hadn't cast in years. All the twenty-year-old black men we knew are about fifty or older now. John lead us to really good people because of his open mind. Yaya DaCosta plays Danny's stepdaughter, China Doll. We would have never auditioned her if we would have known she was from "America's Next Top Model." We don't audition models. But John didn't tell us—and wasn't he smart? So this young woman came in and gave a terrific reading. Actually we could have cast that part three times. I remember John coming to me and saying, "Okay, there are three China Dolls. Maybe we cast one and adopt the other two." Because they were great kids. We picked the right person. Yaya was not only beautiful and really good, but she's also a really disciplined, together young woman. She was surrounded by men. So I was really grateful she was "correct" the whole time we were down there. She's a great young woman.

JS: Brian Williams, the kid who plays Luther, the guy in the hardware store who is so ga-ga over China Doll, is a local kid who plays guitar in his church. He was our connection to the choir that sings in the revival tent. He auditioned and was cast.

Q: Your films seem to mix newcomers with actors you've worked with several times in the past.

JS: The tough thing is that we don't get to make a movie that often and there are so many good actors I've never worked with. I've never worked with Danny Glover, Stacy Keach, Charles Dutton, or Lisa Gay Hamilton before "Honeydripper." This was like a dream cast. When I finish a film, the first thing I do is I ask myself who would I like to work with again. Mary Steenburgen has been in three of our films now. She was an easy choice.

MR: Tom Wright, who plays Cool Breeze the gangster, has probably been in seven of our films. Vondie Curtis-Hall was in "Passion Fish." Daryl Edwards, who plays Shack Thomas the Pullman porter, was in "City of Hope" and "The Brother from Another Planet." They're like the return campers who can explain to the new campers how it's going to go. They'll say, "We always had crummy trailers but it worked out all right" or "Trust me, this hotel is better than the Econo-Lodge in Beckley, West Virginia." They'll also set this level of preparation. The regulars all know their lines right away. They all get it. We're not going to have much time, so don't hold yourself back by being unprepared. It's nice to mix them up. And as you can imagine it was quite a society. There were actors who knew each other's work or had worked together in different places.

JS: Ruben Santiago-Hudson, who plays the drunk guy at the bar, had played Lisa Gay Hamilton's brother in an August Wilson play.

MR: You can't stop Ruben from playing the harmonica, don't even try. There were musicians around so there was a fair amount of jamming at night. The Hampton Inn in Greenville, Alabama was a happy place.

Q: John, talk about the character biographies that both you and Maggie mentioned.

JS: Obviously the bigger the part, the longer the bio. For instance, Danny's was six or seven pages because it was the history of the music, and I sent along cuts of music. He's a guy who's over fifty and I told Danny that Tyrone was born at this time and learned to play the music around this time, and then started playing in clubs at a certain time and then he was here and then there and then here and then there. Also, he was a soldier in World War I—what was that about? He was a soldier and has mixed feelings about it. With some of the smaller characters the bio might be one page or less. Sometimes it will just be, this is when you met your wife and this is where you are now. Sometimes I write something that's more free associative, so it's almost like a short story in the character's point of view. For "Casa de los Babys," I wrote one for Marcia Gay Harden that was basically a bitter rant that her character, a sociopath, would have done. It's about how she hates all the other women and everybody is against her. It was nothing she says in the movie, but it gave her a flavor of how her character thought.

Q: Do you write the bios to create a nexus between the characters for when at certain points their information intersects?

JS: The bios are mostly for the actors and the other heads of departments. So I share the bios with the costumer, the production designer, the DP, people like that. When they're shopping for a character, they have that bio, too. The actors don't necessarily trade bios. What I like is for an actor to come to a scene with his ammunition and for the other actors to come to the scene with their ammunition and to put them in a scene together with their lines and to see what happens.

MR: An actor can prepare a false set of ideas. So it's better to give them some direction, because we don't have a rehearsal period where many questions would come up about their characters. So when they read the bios it's like getting John's pre-direction.

DP: John, one of your skills always has been to balance the stories of the various characters, so do you write the bios to help you with that?

JS: A movie is going to be about two hours, so there is a cross-section of time. What I always like to feel is that people leave our movies thinking, "I could have watched a whole movie about that character or that situation." Any story is a concentration of life. That's why we tell stories. You run into somebody on the street and you ask, "How's so and so?" and he tells a story about him. So if I know more about a character or situation, if I know the background of these things, sometimes I'll just say, "You know what, that should be in the movie. The audience should know that as well, not just the actor." I'm almost thinking out loud as I write the bio, saying, "That should be in the movie" or "That should be clearer," or whatever, and that's another way for me to look at my own work.

DP: Did you find yourself juggling storylines of the characters so that your story is told smoothly?

JS: The main thing I do when I have a lot of characters is a very graphic thing. I write their names around a circle, and then I start drawing lines between them, showing what the characters are to each other and making connections between their individual stories. Then I look at it and I may ask, "Is there any character who has only one line?" The Pullman porter, for instance, is the one who greets Sonny when he comes into town and sends him to Tyrone's juke joint; he is Delilah's brother so is connected to Tyrone in that way; and he's there at the station when Tyrone comes to pick up Guitar Sam. So he's not just an interesting guy who shows up once and disapears. You try to make as many of those lines glue together in plot terms and character terms.

Q: Some of your earlier films, like "Matewan" and "Eight Men Out" were period films made on an independent budget. How has that changed twenty years later?

JS: I've written two historical epics that we haven't been able to raise the money for. If I sit down and write another movie, it's unlikely to be another historical epic. I'm writing a historical epic as a novel right now, set in 1900. It took eleven years from the time I wrote "Eight Men Out" till I made it. In eleven years I'll be 68 years old, so I'm less likely now—when I'm financing my own movies and can't finance a movie that big--to be as ambitious with something I write.

Q: What if someone comes you?

MR: If someone wants to give us $30M to do an epic movie and we get complete creative control, we'd be happy to do it. Absolutely!

JS: I still write movies for directors who have studio financing. I recently wrote a science fiction script for James Cameron about aliens who have been in the White House since the fifties. The great thing about writing for James Cameron is that if he likes something, he'll invent it. So I wrote stuff that doesn't exist yet and though there was no way to shoot it, he'd say, "Yeah, yeah, we'll figure out a way to do it."

MR: People ask us about "Jurassic Park IV," but we're even more excited about this one!

JS: It's not being filmed yet, but we'll see what happens with it.

MR: Meanwhile, let's hope that these two period movies, "Honeydripper" and "The Great Debaters" do well because if they don't then we'll hear "See, period movies don't work." There aren't nearly enough. What's richer than our own history? Yet we seldom go there. It's a shame.

JS: My screenwriting agent told me that one of the studios earlier in the year informed all the agencies that it didn't want any period movies or dramas submitted to it. Meaning, all they want is "Knocked Up" or "Spider-Man" and they don't know how to deal with anything in between.

MR: That pretty much covers "Honeydripper." What has been fun about showing it is that adults love it. It's not for children, not for adolescents, it's not superviolent, it's not supersexy. It's a really good, satisfying story with a really happy ending, which we know doesn't always happen in grown-up movies.

For those Sayles fans--- hes doing an interview on my favorite radio show on the 25th with Elaine Charles. He's going to be discussing Oscar nominations and his films and books. I loved "Honeydripper" so for those of you who want to hear it I suggest listening!If you get New York Radio its on WOR 710 AM on Saturdays, 11pm to Midnight

ReplyDeleteAlso you can hear it online. http://bookreportradio.com/ She always gives a great interview and I'm sure he will give wonderful insight into the movie.

If you'd like an alternative to randomly flirting with girls and trying to figure out the right thing to do...

ReplyDeleteIf you'd prefer to have women hit on YOU, instead of spending your nights prowling around in noisy bars and restaurants...

Then I urge you to play this short video to find out a strange secret that might get you your own harem of hot women:

FACEBOOK SEDUCTION SYSTEM...