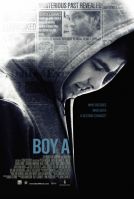

I Give an "A" to Crowley's Challenging "Boy A"

(from brinkzine.com 7/22/08)

Andrew Garfield

Andrew Garfield

I am excited by Wednesday's release of John Crowley's compelling British film "Boy A" because I am curious what the reaction of moviegoers and, to a lesser degree, critics will be. I saw it at the Tribeca Film Festival and thought it was the sleeper of the entire event. I've thought about and even been haunted by the film ever since and I suspect it might hit a nerve with many other people. Crowley and screenwriter Mark O'Rowe made one previous film together, "Intermission," and it too was about how something that happens to one or two people can have impact on many others over time. In "Boy A," a troubled but well-meaning, awkward, and seemingly gentle young man, Jack Burridge (Andrew Garfield), is released from a juvenile detention center where he has been since he was a young boy (Alfie Owen). He no longer uses his real name, Eric, because he and more violent boy, Philip (Taylor Doherty), had been put away for killing a girl in a highly-publicized case that the media has not forgotten fourteen years later. Encouraged by his supportive social worker, Terry (Peter Mullan), he takes a new job, makes friends with Chris (Shaun Evans), wins the heart of a terrific young woman, Michelle (Katie Lyons), and emerges from his shell. But he still worries his identity will be found out and he will suffer the fate of Philip, who was lynched. He seems like a great guy who is totally rehabilitated, but the filmmakers are keeping Jack's big secret from us. We learn his secret and when things go bad for him, we have to figure out the depths of our feelings for him and decide how we want the movie to end. It's an interesting experience for moviegoers. No lumps on logs allowed. Last week I spoke by phone to Crowley (who is in London) about his film.

Danny Peary: Was Jonathan Trigell's novel, from which Mark O'Rowe adapted his tough screenplay, based on a true story?

John Crowley: Yes and no. It was apparently based on a friend of his who was in a juvenile detention center, whom he watched struggle after he was released. His story had a much happier ending than the story of Jack. Also, when he was writing, the murder of the toddler James Bulger by two young boys was in the media a lot. He didn't wish to write about that case, but it filtered down into his mind somewhat. Still all the characters in the novel are fictional.

DP: I read that you wanted to do the movie because you weren't exactly sure if you felt Jack's rehabilitation worked.

JC: No, I did feel the rehabilitation worked. Mark O'Rowe's screenplay had a strong emotional impact on me as I read it because I found myself really wanting things to be okay for Jack because he was rehabilitated. I rooted for him as each revelation about his past came up. As I headed toward the big revelation that I knew would come toward the end, one bit of me kept hoping that he wasn't really involved in the killing of the girl, that he was just an innocent bystander while his friend committed the murder. I couldn't quite believe that Jack was capable of that crime when he was a boy, Eric. When it is revealed he was involved in the killing, that challenges your preconceptions and the relationship you have toward Jack. I found that quite a taut, tense place to be put as a reader. I felt if we cast the movie in right way and didn't sentimentalize it, it would be a unique experience for an audience. Not necessarily an easy one but not a "feel-bad" one either.

DP: In flashback, we see that Eric was involved in the murder, but does that make a difference? I ask because whatever happened took place before Jack goes to juvenile detention for all those years and is rehabilitated. I agree with you that he is rehabilitated, but one scene might make others wonder. In the scene where he comes to the rescue of his work bloke Chris, you may say, "Oh, he's really a great friend," but you also see that he's capable of physical violence.

JC: That's a very interesting point. That scene may make you feel uncomfortable because until then you think he is a very gentle young man. Now you see the aggression. The novel goes into more detail about his time in the juvenile detention center. The reason he is able to fight like that is he spent years around very tough kids there. We didn't include those scenes but let the audience fill in the gap. There was an inherent aggression in him that came out when he was a kid. He had to look after himself when he was young.

DP: I think that scene is important because it is one of two scenes in the movie in which Eric/Jack comes to the aide of his best friend. He doesn't abandon his friends though it means perpetrating violence, against the young girl and, years later, against the bullies who beat Chris.

JC: Exactly. The one profound connection Eric had was with his mate Philip. When Philip cuts the girl's hand, it is immediately after the girl insults his friend, Eric. There is a really strong bond between these two marginalized outcast children, and the second that bond is threatened, even by a girl who is just being mean, they react with violence. And years later when Jack, the grown-up Eric, sees his friend threatened he has a Pavlovian reaction. Friendships are the only things you can rely on.

The script in lots of ways is made up a number of symmetries, our bouncing events off each other at the opposite ends of Jack's life. You balance the two and interpret his life—is he a weak person?; is he strong?; is he a murderer?; is he a hero?: is he an angel?; is he a combination of several of these? How you judge him depends a lot on what you think of rehabilitation and the events in the movie.

DP: He participates in the killing of the girl, which surely surprises many viewers. Is that meant to be a test of the audience so viewers can see how strongly sympathetic they feel toward Jack?

JC: A test is one way of looking at it. I think it's the final piece of information that you need to know about him in order to make judgments. While you're watching his world unravel in the present, and see a witch-hunt underway led by the blood-thirsty paparazzi press, you are perhaps more on his side than at any time in the film. But to have the final revelation dropped into the middle of that—that he was involved in the event—stretches and challenges an audience's degree of forgiveness--and its belief that rehabilitation is possible and that once a person has done his time, he should be allowed to have his life back.

DP: Do you think Jack believes he has paid his dues and has been rehabilitated or is there a part of him that thinks he should still be punished?

JC: Good question. I think there is something in him that keeps him from feeling he's fully entitled to the life that his life force is reaching out for. One could say he has a conscience that's wreaking havoc on him. He's terrified that there's a bad fate waiting for him, similar to Philip being lynched in prison. He feels that either in prison or out in the real world, somebody is going to come and get him. That's indicative on a very deep level of the scar he left on his own psyche when he killed the girl—he destroyed his life when he picked up that knife. What happens with children and violent crime is that there is usually more than one victim. What you're looking at is a young man of twenty-four who is no danger to society and has a huge urge in his body to just go out and live. He wants what we all take for granted. Even though his social worker Terry is so proud of him and is all the time encouraging him, all the time there is a voice in the back of his head going, "Yeah, but…" Jack feels that he might not make it.

DP: The real shame of this is that the worlds of three individuals—his girlfriend Michelle, his best friend Chris, and his social worker Terry—are diminished if Jack is gone from their lives. He had impacted on their lives in positive ways.

JC: There's no question about it. That's the awful thing about what happened when he was a kid, how it destroys several lives years later. An act like that ripples in all directions.

DP: Could this film have been made about Boy B, Philip?

JC: Yes, no question. It would be a very different film.

DP: Could Philip, the more dangerous of the two, be rehabilitated?

JC: Yeah. What you're dealing with are two children who have been brutalized, and that's why they turned bad.

DP: In the production notes, Katie Lyons says this: "I have always shared the view that children are the products of adults and ultimately adults need to accept the blame for the crimes of their children. And these were the themes that particularly stood out in the novel as well as the film." Do you agree with that?

JC: To an extent. But I think to reduce it to that reduces what is compelling about the story and why we need to look at stories like this. We're sort of staring into a mystery, which is: What makes two children murder another kid? You may not accept the explanation that they are pure evil or take the easy way and blame the parents—because a lot of kids come from very bad, abusive backgrounds who don't go out and kill other kids. There wasn't an answer that I could find when I looked at the cases of James Bulger and Mary Bell, a girl who killed two younger boys. It's very hard to explain why they did it, which is why the press went into overdrive about how the young killers were the faces of evil. There is no excuse for these heinous acts but the reaction to them was simplistic. In "Boy A," there is no question that the absent parent and the factor of abuse with Boy B, contributed to the killing, but it can't be reduced to just that.

DP: How did you talk to the two boys about their parts?

JC: Pretty directly. Alfie and Taylor are great kids and very smart. They were twelve going on thirteen so they knew what the film was about and what was going on in each scene. When I talked to them it wasn't with kiddie terms, but in a way that would let them have the information they needed to play the scene. Mostly what I'd talk to them about was the friendship between Eric and Philip, about why they were saying what they were saying, and about what they wanted from each other in each scene. They got the level of comradeship. Rather than go over what the film was about overall, I was specific and kept it simple and I also tried to keep a light atmosphere around them while they were doing very dark stuff.

DP: Did you work as closely with Andrew Garfield or let him figure out the part?

JC: We talked endlessly. He's really smart and loves direction and input, so we had a very strong dialogue right from the second he read the script. He put himself on tape when was doing "Lions and Lambs" in L.A. and we were doing actor auditions in London. It would require a couple of hours to download all the thoughts we explored when we talked about how he would play Jack.

DP: How could he have played the role differently? What were the worries about Jack?

JC: I could have gotten it wrong in casting by choosing someone who was a little less sympathetic. The part was beautifully written but I needed an actor who could provide an extra 20% of Jack's internal life without saying a word. Andrew has that ability and we responded to that when the shooting started. You can almost feel what he's feeling and what you don't feel, you want to feel. You want to get into Jack's head and to know more. He's giving you that much. If I had cast an actor who didn't have that connection, it wouldn't have been as compelling. The other thing is that he talked a lot about how there was a twelve-year-old lurking inside a 24-year-old's body, and how that would manifest itself in subtle ways in every-day life. Michelle responds to that innocence. She finds that quite sweet.

DP: I think your casting of Katie Lyons was perfect. A sexy heroine who isn't slender. Her Michelle is the perfect match for Jack because she sees his inner beauty, as he sees hers. And they like each other's looks!

JC: We saw quite a few actresses. It's a tricky part to cast because everyone at work calls Michelle "the white whale." So we looked for a gorgeous girl who was voluptuous. Actresses starve themselves nowadays. Katie is like a life force, who has done a lot of comedy but not much straight drama. She "got it." She had the toughness and the charm and she's beautiful; and she's real so you believe she's from that world. She's fantastic.

SPOILER ALERT TO BE READ AFTER YOU SEE THE MOVIE:

DP: Michelle freaks out when she learns Jack's identity, but do you think she would respond in the same way if Jack had told her his secret?

JC: No, it would have been different. The way she finds out, she thinks it was a terrible betrayal because they had shared intimacies that suggested there was nothing she didn't know about Jack on a very deep, emotional level. It was shocking to her to have that kind of information dropped into her head—there was an absolute explosion. We can only take what she says herself on the pier in the fantasy scene at the end, which is the truth. She says, "I would have forgiven you." And he says, "Would you?" And she says, "Given time." We accept that because there's no denying that was the real thing between the two of them in terms of love. I think she would have been able to forgive him.

DP: What happens at the end reminds me of "Of Mice and Men," where you want a well-meaning character who has no way to escape before the mob gets to him. It's strange for an audience member to want the sympathetic protagonist to kill himself at the end. You want him to get away in order to kill himself because that's a gentler death. One of the reasons I really like movie is that the audience can't be passive, particularly at the end. It must be involved and somewhat conflicted.

JC: Some people want him to live, even though there's no way that can happen. We have that fantasy scene at the end where Michelle and Jack are together, because an audience needs closure to the story. Having invested so much time in their story, you just need something, even if it's in Jack's head. The thing that struck me when reading the script was how fresh a story it was. Rather than tying things up neatly, the tension grows more unbearable as it gets closer to the end. It's not everyone's cup of tea. A lot of people don't want that from a film. They want a completely different experience, and that's legitimate. It's not the kind of movie viewers encounter very often.

If you're trying to BUY bitcoins online, PAXFUL is the best source for bitcoins as it allows buying bitcoins by 100's of payment methods, such as MoneyGram, Western Union, PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, American Express and even converting your gift cards for bitcoins.

ReplyDeleteYoBit allows you to claim FREE CRYPTO-COINS from over 100 unique crypto-currencies, you complete a captcha one time and claim as many as coins you want from the available offers.

ReplyDeleteAfter you make about 20-30 claims, you complete the captcha and continue claiming.

You can press CLAIM as much as 30 times per one captcha.

The coins will stored in your account, and you can convert them to Bitcoins or USD.