Lee Lowenfish on His Epic Branch Rickey Biography

(from brinkzine.com 12/9/07)

Lee Lowenfish

Lee Lowenfish  Branch Rickey signs Jackie Robinson

Branch Rickey signs Jackie Robinson

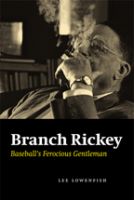

I was a fan of acclaimed sportswriter Lee Lowenfish several years before I first met him. I was pretty much in awe of Lowenfish's "The Imperfect Diamond: A History of Baseball's Labor Wars," which remains one of the most valuable and scholarly sports books ever written. I was grateful that anyone had written on that complex subject, and relieved that the author was both authoritative and accessible. I have returned to that classic book countless times over the years, and even admit to having "borrowed" from it for my own baseball writings. I always was struck by a photo in that book of a smiling Branch Rickey with his arm around the shoulders of someone who never seemed to smile, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The one-time dictatorial commissioner looks anything but comfortable in the grasp of the progressive gentleman who challenged his antiquated legacy with a wrecking ball. Rickey seems to be telling Landis to cheer up because things can't be that bad, but he doesn't seem to care that the Judge, whose strained neck is as wrinkled and twisted as an old turtle's, isn't buying it. That photo has made me want to know more about Rickey than just the familiar Jackie Robinson stories. Fortunately, Lowenfish also wanted to learn more about the man who initiated the farm system ("confounding" Landis, he says) and integrated baseball (which never would have happened while Landis was commissioner.), and was willing to spend years of research and writing to give him his due. The result is the much-needed, definitive biography of one of baseball's most important and compelling figures: "Branch Rickey: Baseball's Ferocious Gentleman."

I recently spoke to Lee Lowenfish about his epic book that would make an ideal Christmas present for the baseball fanatic on your shopping list—or you.

Danny Peary: Was it more than simply a historian's interest that led you to write such a detailed book about Branch Rickey?

Lee Lowenfish: Like many people, I had been soured on baseball by the 1994-95 strike. The greed and ego on both sides, billionaires versus millionaires, turned me off. But I couldn't get the game out of my system and on a trip to Cooperstown around 1996, an exhibit on black baseball, and the Jackie Robinson story, which I had written about 20 years earlier, piqued my interest again. I realized that Branch Rickey hadn't been written about since Murray Polner's 1982 biography, and though that had been informative I thought there was more to be said, especially about Rickey's baseball life. Ditto after reading Arthur Mann's bio of 1957. So in 1997 I gave a talk on Rickey's ownership battle with Walter O'Malley in Brooklyn at Long Island University-Brooklyn, where I dug up the story of the Dodgers' third partner, Pfizer chemical mogul John L. Smith, a real baseball fan whose death precipitated Rickey's departure. Then in 1999, I went to Ohio Wesleyan where Rickey's family was honored, and I was on my way.

DP: Would you have chosen your oxymoron title before you did the research, or did Rickey already have the reputation as a "ferocious gentleman?"

LL: I ran across the term "ferocious gentleman" in a newspaper account of Rickey's defending Leo Durocher's attack on a fan who allegedly had said disparaging terms a mother would not like to hear. I also heard Roger Kahn use the term in a tape of a 1994 forum on the Dodgers at 92nd Street Y. Later in interviews with some of Rickey's grandchildren, I was told that it was an apt description. I tried to not use the term "Mahatma," a clever moniker given to him by sportswriter Tom Meany in Brooklyn, because he was not a pacifist. He was an idealist but not a pacifist, and there is an important difference.

DP: People forget how long Rickey's sports career was, dating back to when he was a pretty bad catcher. Did you come up with surprises while researching the early part of his life?

LL: I was surprised at his experience in coaching other sports, especially football. I knew about his work in football at Ohio Wesleyan, but he also coached the sport at Allegheny in western Pa., and assisted Fielding "Hurry--Up" Yost at Michigan when he wasn't coaching baseball and getting through three years of law school in two years. To me an essential tableau of Rickey is him--passionate, always wanting to win--down on the floor with Yost and going through last week's game and preparing for this week's game late into the night.

DP: What are the most important themes that run through the book as we move from the young Branch Rickey to the Rickey who owned the Dodgers and integrated baseball to the post-Dodgers Rickey as the GM in Pittsburgh, to the post-baseball Rickey? Was he basically the same man or did he change or adapt in certain ways?

LL: I recently gave the keynote address at the State Historical Society of Missouri's annual conference on the campus of the University of Missouri in Columbia. (It was the same town where Rickey collapsed giving his last speech at a banquet in which he and George Sisler were elected to the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame in November 1965. It was an eerie connection, but I came though my speech without illness!) I called my speech, "A Consistent Player and A Consistent Christian." When Rickey was interviewed by a sportswriter in 1906, when he was a member of the St. Louis Browns, he expressed his goals in life in terms of consistently being a good player and good Christian. If you extend "player" to mean executive, I think he fulfilled his ambition. I don't think he changed very much over time. He would have adapted to modern technology very well-- he was a tinkerer way back when they came up with sliding pits, batting cages and other contraptions to make a player better and more consistent. He also pioneered the batting helmet. (Part of his bitter feud with Larry MacPhail was due to MacPhail's claim that after Joe Medwick was beaned in 1940, he brought in helmets, too, but nobody did it as extensively as Rickey did in the early fifties in Pittsburgh.) Rickey would have loved the rapidity of the internet and the emergence of international players through major league baseball. He would have been aghast of course at the amount of money players make and how it might make some of them complacent. But I think a younger Rickey might have done surprisingly well in today's baseball.

DP: If Branch Rickey hadn't integrated baseball, would he have had a positive legacy? Is for instance, creating a productive farm system for the Cardinals, and then Dodgers, something baseball fans should praise him for?

LL: I think the farm system is especially relevant today because it showed that a team without bottomless monetary resources could compete and succeed through wise scouting, evaluation and development. In Rickey's St Louis prime, the Yankees and Giants and other rich teams were buying a lot of players, but not developing them Rickey's farm system was his means of signing players for little cost and developing and keeping them in the minors "until they ripened into money." It was an ingenious idea that other organizations began to imitate by 1930s. I think that if the Continental League had succeeded, it would have been another worthy legacy—in any case, his effort led to expansion in the major leagues and widening the audience for the great sport of baseball that both Rickey and I love.

DP: Do you think it was important for Rickey to be the first to integrate baseball rather than letting Bill Veeck or someone else be the one?

LL: I think the beginning of integration was an idea whose time had come and Rickey seized the opportunity. He sincerely felt that if one million black people had been in uniform during WWII it was entirely fitting for some of them to have the chance to play baseball as equals. Once he got the lead on the best players he was more than happy for Veeck and Horace Stoneham with the Giants and Lou Perini and company with the Boston Braves to join his company. [See Lowenfish's story "Two Cheers for Horace Stoneham" in "The Glory Days," a book of essays that was published in conjunction with the exhibit of the same name at the Museum of City of New York.] Rickey was supremely satisfied that he beat his rivals to the punch on the black players but he was equally happy that he hadn't cornered the market so the idea would spread.

DP: When did he start thinking of the idea? And did he ever say it wouldn't work and think of postponing it?

LL: It is hard to know exactly when but certainly in his heyday with the Cardinals in the 1920s and 1930s he saw Negro League players like Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell and others play. In his only book, "The American Diamond," published the year he died, 1965, Rickey described Paige as having immense devotion to baseball; only Honus Wagner, he said, was comparable in that regard. He saw the rise of Joe Louis in boxing and Jesse Owens in track and field, but being a conservative Methodist and Republican, he was ultra-cautious about how integration should proceed. Cynical agnostic or atheistic big city people may scoff at this, but Rickey, a teetotaler, was keenly aware at how Prohibition made matters worse for the temperance movement. So in his secret scouting during World War II he tried to find the right kind of black player off the field, proud but willing to take slings and arrows, even martyrdom, for the cause.

I don't think Rickey ever thought "the great experiment" wouldn't work. Again, to modern audiences this term sounds condescending, but Rickey was just naturally Victorian in his utterances and meant no offense. (By the way no one seems to know where that term came from. If anyone knows, do inform me.) I do think he was not convinced at the outset that Jackie Robinson had the forbearance he wanted in the race pioneer. But when the issue became a political football in the 1945 NYC mayoral campaign, he had to go ahead with the announcement of Robinson alone signing in late October 1945.

DP: Since 1946-47, everyone in and out of baseball has debated whether Rickey integrated baseball for altruistic (perhaps Christian-based) reasons—Don Newcombe told me that he thinks this was the case—and/or to attract African-American fans to ballparks and dramatically increase revenue.

LL: Newcombe is absolutely right. And if my book does nothing else (and of course I hope it does more), it should put to rest that Rickey's motive was purely economic. Even if it was, it was the right thing to do and the economically profitable thing to do. We should celebrate that lovely congruence and not nit-pick at it.

DP: Is it a spot on Rickey's reputation that he didn't reimburse the Negro Leagues for signing their players, while Veeck did?

LL: As we all know, Rickey was frugal and he wasn't going to pay for anything that he didn't have to. There are letters in his archives at the Library of Congress in which Robinson, Roy Campanella, Roy Partlow, and others he signed from the Negro Leagues write him that they are not under contract to anyone in the accepted legal sense. Still it should be noted that he did pay $3,000 for Partlow to Ed Bolden of the Philadelphia Stars, and in August 1947, $15,000 to the Memphis Blue Sox for Dan Bankhead's contract.

As for Veeck, it should be noted that only when Robinson showed he was the real goods by May 1947 did Veeck jump into the market and start enthusiastically signing black players. In late April when Robinson was struggling and not yet a proven major leaguer, Veeck gave an interview in which he basically said what Bob Feller had said--that Robinson looked more like a football player than a baseball player and may well not make it.

DP: Talk about the Rickey-Walter O'Malley power struggle and whether there was a chance Rickey would win it.

LL: The key to Rickey staying in Brooklyn was John L. Smith, the silent partner. Smith did not like Rickey's extravagant expenditures, especially with the football Dodgers but he admired Rickey's knowledge of baseball and his genuine Christian conscience and charitable activities. If Smith had lived, it would have been far harder for O'Malley to ease Rickey out.

DP: Do you think Rickey would have taken the Dodgers out of Brooklyn? And is it possible that O'Malley traded Jackie Robinson to the Giants (forcing him to retire instead of going to the enemy) to get this Rickey disciple out of the way for when the Dodgers moved forward with plans to move?

LL: Rickey never would have considered leaving Brooklyn. Nor would have Smith. He lived less than a mile from Ebbets Field and was that rare bird, a genuine fan-owner who would come into the clubhouse on a Sunday and wave a pennant and generally bring good cheer.

The Robinson trade was after the 1956 season and the Dodgers were halfway out the door already. Robinson was near the end as a player, too, so I don't think it had more than tangential relationship to O'Malley's grand plans. But talk about "what-if" history! Robinson did say he would have liked to play with Willie Mays. How about that tandem on one team?! Even an aging Robinson.

DP: What were Rickey's feelings about leaving the champion Dodgers and going to the lowly Pittsburgh Pirates?

LL: He was very sad. "Would a man of my age, 69 on December 20," he told a reporter, "after having remained here for eight years, and enjoying his job, want to pull out?" But Rickey could not face idleness, so deeply engrained was the Protestant Ethic in him. He accepted the Pittsburgh challenge and owner John Galbreath's lucre that included a chance to buy property for a family gathering place on the remote huge fresh water Manitoulin Island in Northern Ontario--part of which today is known as Rickey Island.

DP: If Rickey was so driven to integrate baseball, why did he do so little to integrate the Pirates, taking years before even the lousy Curt Roberts joined the team? Drafting Roberto Clemente from Brooklyn also came late.

LL: He comes to Pittsburgh and finds a team with no real farm system and the best players soon to be drafted for the military. He's up a creek and ownership starts souring on him pretty early. But he is a battler, begins to develop a farm system, adding good white, black, and Hispanic players. Unfortunately, Roberts and outfielders Felipe Montemayor from Mexico and Carlos Bernier from Puerto Rico don't pan out. Rickey did try to find black players. In fact, of the fifty-five scouts he hired, twenty-two were black. But by 1952 his ownership was tightening the purse strings and wouldn't pay the bonuses needed to sign such talents as Ernie Banks and Frank Robinson. Still, he did have impact on the future of the team. Though Rickey was gone by 1960, the team that beat the Yankees in the World Series had a Rickey touch—from its one black, Clemente, and Roy Face (also plucked from the Dodgers) to Dick Groat, Bill Mazeroski, Bob Skinner, et al.

DP: Talk about Rickey underpaying the Dodgers, having the minimum-salary Rickey-Dinks in Pittsburgh, and famously cutting home-run champion Ralph Kiner's high salary and then trading him. Was he cheap, frugal, or conniving, or all three?

LL: Rickey's firm belief--his ideology really--was that hungry ballplayers were the best kind because they would be competing furiously for the World Series share. You don't have to agree with this, of course, but what fascinates me about Rickey is that he was so old guard in that view--see Connie Mack, Calvin Griffith, Ed Barrow, and George Weiss for that matter--but was so progressive and enlightened in other ways. The Kiner contract he inherited from owner John Galbreath, and because Kiner was the one fan attraction Rickey had to keep him longer than he would have liked to. Given that his career ended two years after Rickey traded him, Kiner was the perfect example of someone Rickey preferred to trade a year too soon instead of a year too late.

DP: Did Rickey ever try to acquire another franchise or be the owner or GM of an expansion team? What about Rickey and the proposed Continental League?

LL: Bill Shea wanted Rickey to be the general manager of the Mets. The first GM of the Mets was Rickey's nephew-in-law Charles Hurth, the former president of the Southern Association, and at one time the youngest chief executive in baseball. But Rickey did not want it thought that he sponsored the Continental League only to get a job in the existing leagues. (My source for this is Charles Hurth Jr.) As you can read in my chapters on the Continental League, Rickey rued expansion the way it was applied. It reminded him of the twelve-team National League of the 1890s when all expansion did was add more second-division teams.

DP: Was there a point where Rickey became passé? Did he feel phased out—as really was Jackie Robinson--or was he content with his legacy?

LL: Rickey realized in the 1950s that the game was entering a new phase in which the economic bottom line was more important than the patient development of farm systems. But he craved to be at the center of some ambitious enterprise, which is why he came to Pittsburgh and later took on the Continental League job, and when that failed he went back to St. Louis to try to run the Cardinals even though he was an ailing man in his eighties. With Bing Devine already in place, he should have realized that it would be an awkward situation at best. But his legacy was not on his mind. He wanted to live each day as if he were going to live forever, and having some meaningful role in baseball was always important to him. As for Robinson--he and his wife Rachel had larger, non-baseball goals on their minds, so he wasn't worried about being phased out in baseball, especially when his mentor Branch Rickey wasn't in much of a position to help him.

DP: When Rickey died in 1965 while giving a speech, was he still close to Robinson? And was the baseball world upset or did no one really care?

LL: Rickey and Robinson always remained close though they did not see that much of each other after Rickey left Brooklyn. Robinson always called Rickey the father he never had and Rickey returned the compliment to one of his favorite idealistic and competitive "sons." Branch and his wife Jane Moulton Rickey attended Robinson's induction into the Hall of Fame in 1962, and Robinson cut short a European trip to fly home to Rickey's funeral in St. Louis. The baseball world sent many dignitaries to the funeral but it certainly was not as big news as it would have been fifteen years earlier.

DP: If you could ask Rickey five questions that you still don't know the answers to, what would they be?

LL: 1. Did you ever tell Sam Breadon, the St. Louis Cardinals owner who fired you as field manager on Memorial Day 1925 to allow you to devote your entire energies to the player development system, that it was a wise decision?

2. If philanthropist-oil man Lew Wentz had bought the Cardinals from Breadon after the 1934 season, would you have stayed in St. Louis indefinitely and tried to racially integrate that team?

3. If Mayor LaGuardia hadn't forced your hand during New York's political campaign season of 1945, would you still have signed Jackie Robinson as the sole race pioneer or would you have signed other black players at the same time?

4. If you had known how barren the Pittsburgh farm system was in 1950, would you have accepted that enormous rebuilding job?

5. How close were you to raiding the National and American Leagues in 1960 when it became clear that the existing leagues were not going to help the Continental League acquire any players?

DP: How can people get hold of your book?

LL: My book is available at the website of the University of Nebraska Press:

www.nebraskapress.typepad.com, and at amazon.com and bn.com.

I am available for autographing at leelow627@earthlink.net

dannypeary@aol.com

There's shocking news in the sports betting world.

ReplyDeleteIt has been said that every bettor must watch this,

Watch this or quit placing bets on sports...

Sports Cash System - Advanced Sports Betting Software.